Front and Center Vol. 2 No 2 February 2023

FRONT AND CENTER

Vol. 2, No 2, February, 2023

Mission

Honoring the legacy of Carolina Marines and Sailors and inspiring future generations.

A Message from the CEO

2023 is off to a great start for the Carolina Museum of the Marine. The team that will build the museum is in place:

- HICAPS: Construction Manager

- CJMW: Architect

- Ralph Applebaum Associates: Exhibit Designer

- Samet Corporation: General Contractor

We are moving out on pre-construction activities and exhibit design. It is an exciting time, and much progress is being made, but your continued support remains vital.

Also, we recently published our first two courses of instruction on our website (MuseumoftheMarine.org): The Art of Thinking and Political Thought in American Tradition. If you enjoy the essays, the courses are a great way to learn more. Please watch and provide us your feedback. With our studio complete, more content is on the horizon.

Semper Fi,

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret)

Chief Executive Officer

Situation Report

Carl Schuemann (Samet Corporation), Matt Krupanski (seated, Ralph Applebaum Associates), John Drinkard (CJMW Architecture), Nick Applebaum (Ralph Applebaum Associates), Tom Calloway (CJMW Architecture ), and BGen Kevin Stewart (CMOTM | AGCI).

Not pictured, David Bollenbacher (Samet Corporation) and SgtMaj Joe Houle (CMOTM | AGCI), both of whom are moving targets when a camera arrives…

Our formidable construction manager, Dave Smith of HICAPS, keeps everyone on task and moving out sharply.

CWO5 Lisa Potts (CMOTM | AGCI), Carl Schuemann (Samet Corporation), John Drinkard (CJMW Architecture), and Matt Krupanski (Ralph Applebaum Associates)

Want to stay informed of our progress?

Al Gray Marine Leadership Forum Launches Classes

The Art of Thinking: How to Think to Think, Not What to Think

This introduction to the Art of Thinking and why thinking matters can be viewed in its entirety or one segment at a time. Segments are approximately 15 minutes. Learn how to think, not what to think.

Interview with CEO Kevin Stewart

We are honored to continue work with Rooks Advertising of Lakewood Ranch, FL as we launch the with courses and interviews. This month’s issue of FRONT AND CENTER features an interview with CEO, BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret).

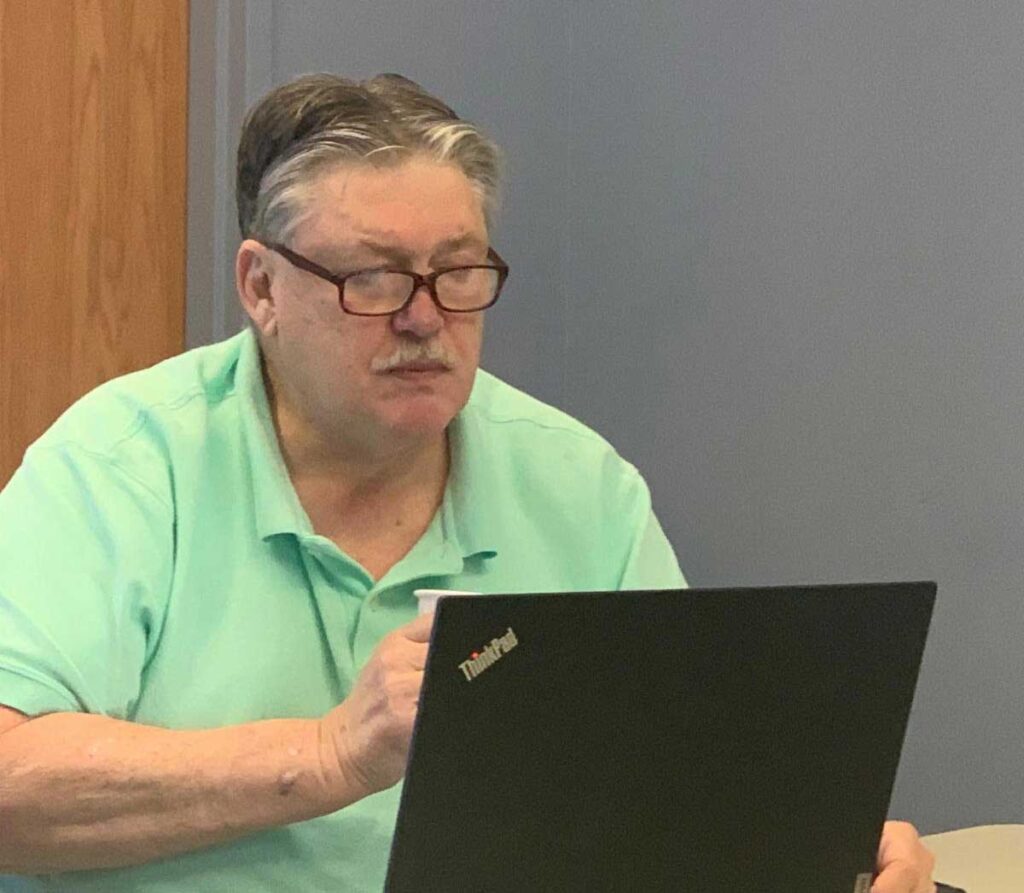

Dr. Jim Danielson interviews CEO Kevin Stewart.

“No Place I’d rather live…”

Special thanks to Sack Family Foundation and Jacksonville Tourism Development Authority for their support of the creation of the studio!

Stay tuned next month for an interview with SgtMaj Joe Houle, USMC (Ret).

Kevin Stewart, Jim Danielson and David Rooks prepare to record classes and interviews. Visit our website for new additions.

Al Gray Marine Leadership Forum Essays

The intent of these essays is to create civil discourse and spur thought. In line with our mantra of “teaching how to think, not what to think” these essays are complex, and the issues addressed are difficult to navigate without sparking some disagreements.

We welcome this, as we work to inspire principled and committed leaders.

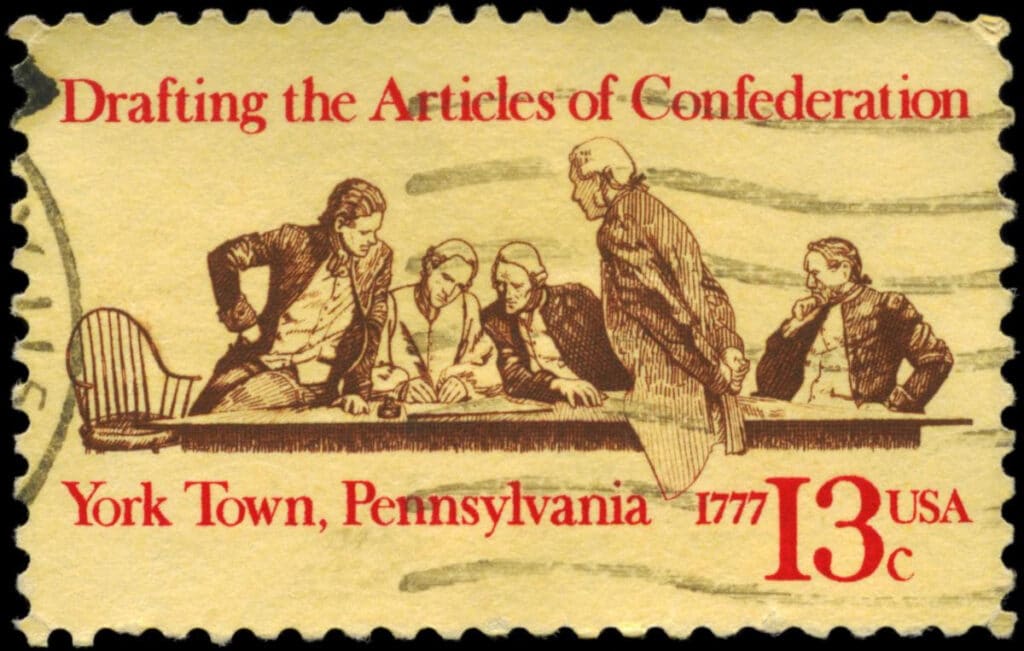

Founding Principles of the United States:

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union

by James Danielson, PhD

USMC Veteran

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union is the first constitution of the United States. When the colonies of British America secured their independence from Great Britain, each colony became a free, sovereign, and independent nation, a fact that is expressly recognized by the British government in the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Americans at the time were agreed among themselves that they needed some kind of political union for common defense and to facilitate free trade among the states. In the early years of American independence, Britain, France, and Spain were active in North America, and as imperial powers, were a danger to the American states without a political arrangement among them for mutual defense. For example, the Americans did not so much defeat the British in our war for independence as Britain simply gave up the fight. At the time, the British Empire was at war with multiple nations and the shoot-out with the Americans was seen as an unnecessary distraction. There was discussion among the British when the decision was taken to let the Americans go that when things calmed down elsewhere in the Empire, they could then commit the necessary resources, should they desire, to re-imposing British rule over the former colonies. This danger was acknowledged as well as the possibility that any single state could be conquered by France or Spain, and so the need for a union for common defense was clear to all (possibly excepting Rhode Island which was reluctant in the early years to join the union).

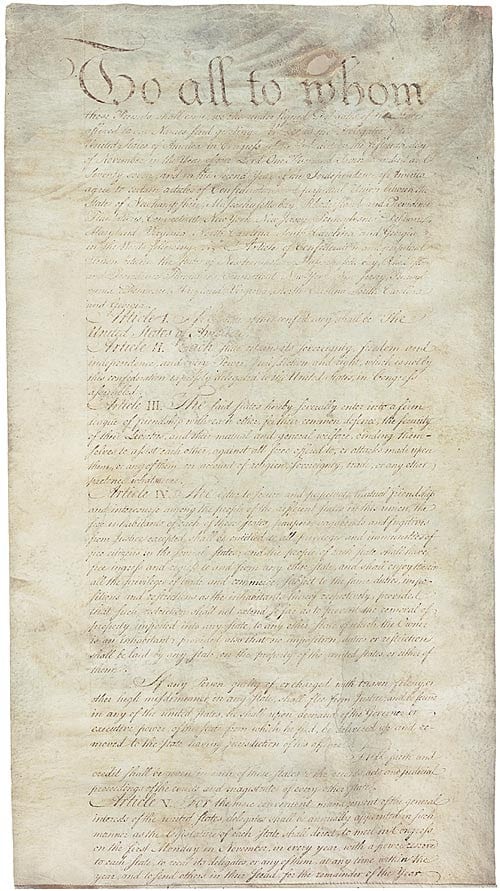

When independent sovereign states enter into alliances, what is the nature of the agreement among them? The answer to this question is suggested in the title of the constitution agreed to among the states. The Articles of Confederation established a “perpetual” union. But the perpetual union established among the thirteen American states in 1781 ended in 1788 when nine states withdrew from it (without charges of “treason”). What, then, is a “perpetual union”? The Articles of Confederation, like the Constitution of the United States, was a compact among sovereign states. A compact (a contract) is said to be perpetual when it has within it no term of duration. If a compact does not stipulate an end date, it is said to be a compact of perpetual term, or a compact-at-will, which means that the parties to the compact may negotiate a departure from it as each party deems proper. There is no such thing in law as a compact into which people may enter at will, but once a party to the compact, may never leave on pain of force and violence. Moreover, no living generation may agree to a political compact that binds their descendants forever thereafter. It is odd indeed to say, following the Declaration of Independence, that the authority of government rests on the consent of the governed, and then insist nevertheless that future generations must abide by the current political order whether they like it or not. Every compact must provide for rescission, for the parties to it to withdraw from it, otherwise it is not a compact but an instrument of continual political control which cannot exist among a free and sovereign people. In other words, where such an instrument of political control is in force, the people living under it are not free, regardless of official rhetoric. This shows us what people in our founding generation understood well: for freedom to flourish, government must be kept to its narrow and proper functions, and thus usurpations of power must be resisted the moment they appear. The concern here is the dreaded precedent. If we allow an unlawful act by government, we have accepted that government may act outside the law that governs it, and thus there are no functioning limits on its power.

The Articles of Confederation was designed to establish a general government that was sufficiently bounded that its officers could not grow its power. The Congress had a house of delegates but no senate. There was no executive and no court (except courts for trying acts of piracy and other felonies committed on the high seas). The reason for this was simply that each state had a governor and its own courts, so a federal executive and supreme court would add nothing but opportunities for federal mischief. The Articles of Confederation were formally adopted by the states on November 15, 1777, but didn’t go into effect until 1781. The document contains thirteen articles of which we will consider the ones that express the political principles animating it.

The first Article gives us a name: “The Stile of this confederacy shall be ‘The United States of America’.” The second Article declares the new confederacy to be based on the principle of federalism that will be expressed in the tenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States. “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.” So the general government has only those powers that are “expressly delegated” to it in the Articles of Confederation. Every other power, no matter what, is retained by the states individually and to the people thereof. Thus every act of the general government that is not grounded in the basic law of the Articles is a usurpation of power and not a law at all, and so the means of dealing with such a usurpation is to correct the government immediately by declaring the offending act to be “null, void, and of no force or effect.” It is foundational to a government founded on the principle of federalism that sovereign, independent states retain at all times the power to nullify unconstitutional laws of the general government. Recall that the Articles of Confederation is a compact among sovereign nations, and so when the general government acts beyond its stipulated authority, it violates the compact and so its act has no force within the common agreement among the states. When a compact is violated, the parties to it are released from obligation to the agreement unless the parties correct the error. Under the Articles, and under the Constitution, the method of correction is to declare the unlawful act to be null and void, and to refuse to comply with it. The general government under the Articles and the Constitution is an artificial corporation for specified and limited purposes and nothing more. It possesses no sovereignty of its own because the general government is not a party to the compact, but rather is an agent of the sovereign states that produced it.

The third Article explains the purpose of the confederation. “The said states hereby enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defence, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretence whatever.”

A league is a gathering of independent persons or entities for agreed-upon purposes, and in this Article the members are clear to enumerate the purposes agreed to. There is nothing in this Article that confers on the Congress authority to educate children, run hospitals, manage agriculture, build roads and bridges, provide for the retirement of the aged, or whatever else people in government may want to do. All such concerns, according to the second Article, are matters for the people of each state to decide for themselves. The sovereign people of South Carolina may have different ideas about education than do the sovereign people of New York, and so the insistence on having uniform laws on such matters emanating from the center is a frightful intrusion on the sovereign freedom of a state. The reference to general welfare, also in the Constitution of the United States, is, of course, intolerably vague, but in the Articles of Confederation it remains that whatever people in government might assert “general welfare” to mean, the general government has only those powers “expressly delegated” to it. In the Articles of Confederation, there are no implied powers.

Article five provides in part for selecting and regulating delegates to the Congress. Each state shall have no fewer than two and no more than seven delegates. When Congress is in session, it is the responsibility of each state to provide material support for its delegation. Moreover, delegates are to be selected by a method to be determined by each state, and each state legislature possesses the authority to recall its delegates at any time and to replace them as deemed proper. This, of course, is intended as an absolute brake on confederal usurpations of power. If it came to a contest between Congress and the states, the states may simply recall their delegates and put an end to the business of the offending legislative body.

Perhaps what was most objectionable about the Articles of Confederation to the nationalists of the time, like Alexander Hamilton, was that the Congress had no power to tax. The revenues for operating the general government were to be raised by the state legislatures according to a formula laid out in the eighth Article. However, if a state decided to send less money than determined, and arguably even none, the general government had no recourse at its disposal. This made many men of the governing class at the time seethe with frustration. Gouverneur Morris of New York reportedly insisted that if it helped get rid of the Articles of Confederation, he would argue that under its government, water wouldn’t boil. Happily, no one in office today would ever think this way…

After a few years of government under the Articles of Confederation, there was much displeasure expressed about it. True federalists, like Thomas Jefferson, very much liked the Articles for its constraints on government, but others, including George Washington who feared the general government under the Articles was too weak to provide for the common defense, wanted to replace the document with one of “a more energetic government.” Importantly, one with power to tax. There were a few efforts to organize a convention for a new constitution, but opposition to it was too great for success. At length, James Madison and others got agreement for a convention in Philadelphia in 1787 to prepare amendments to the Articles of Confederation for the states to consider. When the delegates convened in May, their first act was to swear themselves to secrecy (James Madison died without publishing his notes on the convention). Although it was a hot summer in 1787, the delegates kept the windows closed in the room where they met so that people outside could not hear them. The delegates then proceeded to write a new constitution for the United States, one of a more energetic government. Those Americans who wanted to keep the Articles, it seems, went along with the new constitution, with amendments, because they feared the union would break apart over dislike of the Articles of Confederation among nationalists, and the loss of security within the union was thought more grievous than the dangers to liberty of the new, more energetic government. So a new constitution was written and ratified, and Americans have been coping with the stresses of interpreting it ever since.

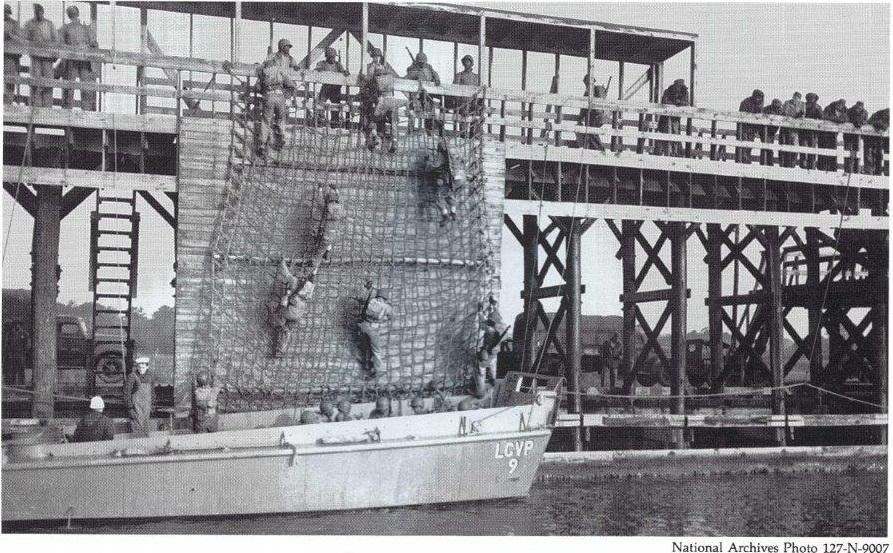

U.S.S. NEVERSAIL

by LtCol L.J. Kimball, USMC (Ret)

Camp Lejeune’s initial, $14.5 million, four-phase wartime construction was completed by 18 December 1943, thereby converting the approximately 111,000-acre tract of Onslow County’s wet and forest, and farm lands into the east coast divisional training area envisioned by its purchase on 15 April 1941 to train the 1st Marine Division (MarDiv) for expeditionary operations overseas. The current Camp Lejeune has changed considerably since its predecessor eighty years removed as a result of social, political and particularly technological dynamics and the impact of military developments. Entire older areas and buildings previously constituting the physical plant have disappeared to be replaced by newer construction along with supporting road networks and infrastructure, and existing buildings substantially renovated.

Accompanying the removal of some of the older facilities, their access roads no longer required for their designed purpose and not impinging on subsequent construction, the old road names remaining as historical artifacts in themselves serve as a reminder of earlier missions, sometimes forgotten, fulfilled by the long absent facilities.

Such are “Parachute Tower” and “Mockup” Roads; Parachute Tower being the more familiar since it still leads directly off Holcomb Boulevard and into the recently constructed Wallace Creek Area. Originally, it led to the Parachute Training Area where in past years three 250-foot steel towers dominated Main Sides’ skyline and where several hundred “Paramarines” were trained in response to the Marine Corps’ brief flirtation with vertical envelopment by parachute as a means to enhance amphibious capability. Here, an east coast parachute school was established on 15 June 1942 and one of the four Marine Corps parachute battalions, the 4th Parachute Battalion, was activated. The school, however, experienced substantial birthing problems and was little utilized in comparison to its west coast sibling, being disbanded on 1 July 1943 after only thirteen months of comparative inactivity. The towers fell to the welders’ torch within the decade with no further justification that would merit their continued existence as well as the Corps’ abandonment of the parachute program.

Less known because of its relatively remote location off Sneads Ferry Road is Mockup Road, its entrance approximately 1000 yards south of that of the Onslow Beach Road. And it currently goes nowhere, just to a bleak, barren clearing bordering on the western bank of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (AICWW), opposite to what was originally the long-removed Signal Schools Facility Area on Onslow Beach, more recently the former home of the 2nd Reconnaissance Battalion. The mockup, shortly to receive the popular sobriquet the “U.S.S. Neversail,” was a crucial, unanticipated and consequently unfunded item in the construction budget necessitated by a monumental shift in the naval situation in the western Atlantic.

Following Germany’s declaration of war on 11 December 1941, America’s sea frontiers, previously restricted from attack by Germany’s deadly marauding submarines, became a target-rich environment and American as well as other Allied shipping suffered accordingly. During the early months of 1942, monthly sinkings off the east coast alone surpassed 100,000 tons a month and overall, in the first six and one-half months, over 360 ships were lost. This presented an immediate problem for Camp Lejeune’s 1st MarDiv which, as the Marine component of the Atlantic Fleet’s Amphibious Force, was trying to achieve the capability to conduct amphibious operations in support of the various contingency plans with which it had been tasked, and under trying circumstances, such as having its operational integrity compromised by having component units siphoned off for other contingencies.

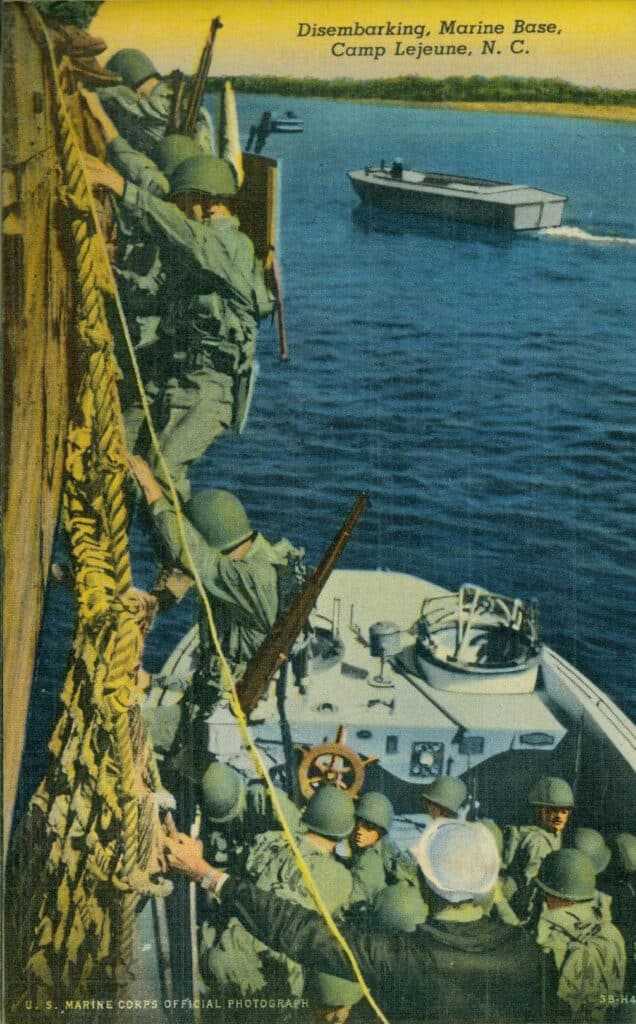

The Marine Corps, particularly the 1st MarDiv and its predecessors, had during the decade preceding the war been seminally involved in developing and refining what was considered to be the most significant tactical innovation of the 20th century, a viable doctrine for the conduct of amphibious operations. Now the training to achieve that capability was being functionally curtailed by the inability to rehearse one of the key phases of an amphibious assault, one of the most difficult and dangerous, the actual projection of the landing force ashore onto a hostile shore. Rehearsing would entail moving the landing force off the transports and into attendant landing craft effectively and efficiently, and transporting them to their assigned beaches, skills requisite to both the Marines and sailors crewing the boats. And, a skill that would absolutely require transports for the necessary training. The Atlantic Fleet had only six transports to its name, none of which could be risked in the dangerous Atlantic waters off the eastern seaboard to the voracious German submarines.

“How in the hell are we going to get in our amphibious training” thundered Col. Graves B. Erskine, the amphibious force chief-of-staff, when apprised of the situation. He shortly contrived a solution, which he sketched on the back of an envelope and presented to the constellation of stars that fortuitously were present in Camp Lejeune at the time, the commanding general of the 1st MarDiv (MajGen Archer Vandegrift), the commanding general of the amphibious force (MajGen Holland M. Smith) and the Major General Commandant of the Marine Corps (MajGen Thomas Holcomb), all of whom were in concurrence. His idea was to build a replica assault transport, a mockup, affixed to the bank of the AICWW on one side with the other side in the water simulating in all respects the side of an actual transport. Marines could practice disembarkation by descending using cargo nets into waiting landing craft subject to real wave motion, augmented by other landing craft speeding up and down the waterway near the mockup, true “wet-net” training. Loaded landing craft would then head down the waterway and motor through the New River inlet into the Atlantic, letting the boat teams and crews experience the reality of ocean waves before assaulting Onslow Beach.

Funding was an immediate concern but the redoubtable Quartermaster General, MajGen Seth Williams, wrangled $173,000 for the project and with the use of division assets, the 1st Engineer and 1st Pioneer Battalions, the mockup became a reality in early 1942. The three-deck mock up, with a total deck area of 7802 square-feet, was 362 feet long with decks varying from sixteen to twenty-two feet above the water. All the landing craft and the crews were Coast Guard, which had first come to the New River to join the 1st MarDiv on 8 December 1941, and tasked with providing all necessary waterborne support particularly that including the training of Marines. Another distinction held by Camp Lejeune is that it housed at Courthouse Bay, in close proximity to the mockup, to their mutual benefit, the Coast Guard’s only landing craft school along with all the facilities to operate and maintain the Coast Guard’s flotilla of landing craft.

Wet-net training was hazardous. Fully loaded Marines, incumbered by the weight of their weapons and equipment that tended to pull them away from the cargo net, being jostled and stepped on by other team members, having at best a tenuous grip on the unsteady net and having to jump from the bottom of the net into a sometimes-gyrating landing craft, faced many perils, even before facing the enemy. But this was how in the early years of the war the landing force got ashore, and this is why the mockup was important. And this is how the Marine Corps lost its first Montford Point Marine on 20 August 1943.

All Fleet Marine Force units were obliged to undergo wet-net training. On 20 August it was the turn of the 51st Defense Battalion’s Seacoast Artillery Group in preparation for deployment overseas. Cpl Fraser was a well-respected and popular artilleryman in a 155mm field gun battery and had been selected for promotion to sergeant. He was a 1939 graduate of Virginia Union University, the captain of the basketball team there and the star pitcher on Montford Point’s baseball team. Fraser for reasons unknown fell from the cargo net and into the landing craft, subsequently dying from the resultant skull fracture. As the first African-American to die in the uniform of a U.S. Marine, his legacy might well have been forgotten except for the Carolina Museum of the Marine, which as part of its mission serves to preserve and promote the proud history of the Carolina Marines and will tell these stories as with that of the U.S.S. Neversail. Perceiving a historical oversight, the museum petitioned Headquarters Marine Corps and received permission to rename a street in Montford Point to Fraser Road. This was accomplished with appropriate ceremony on 22 June 2007.

With the Battle of the Atlantic won, a relative abundance of amphibious transports now available and the Marine Corps focus now directed primarily to the Pacific along with its major training activities to the west coast, the mockup fell into disuse, having succeeded in performing a needed task in a critical period of Marine Corps history. Gen H.M. Smith penned its epitaph: “Over its sides graduated thousands of Marines who carried the lessons they learned in North Carolina to the surf-swept atolls of the Pacific.” Neversail was stricken form the base’s plant account by June 1944 and removed sometime in the 1950s.

REFERENCES

Robert B. Asprey. Once a Marine: The Memoirs of Gen A.A. Vandegrift, USMC. W.W. Norton & Co, 1964.

G.W. Carr, et.al. Completion Report Covering the Design of Camp Lejeune…Contract NOy 4751, April 15, 1941-September 30, 1942. Carr and Grainer, 17 Jul 1943.

LtGen Erskine B. Graves. Transcript of Interview by Oral history Unit, Hist Div, HQMC, dtd 13Jan75.

Marines Making News…

Visit Marines.mil for up-to-date information about United States Marines who are making news.

Please join us in supporting the mission of

Carolina Museum of the Marine

When you give to our annual campaign, you help to ensure that operations continue during construction and when the doors open!

Stand with us

as we stand up the Museum!

Copyright February, 2022

Carolina Museum of the Marine

2022-2023 Board of Directors

Executive Committee

LtGen Gary S. McKissock, USMC (Ret) – Chair

Col Bob Love, USMC (Ret) – Vice Chair

CAPT Pat Alford, USN (Ret) – Treasurer

Col Joe Atkins, USAF (Ret) – Secretary

Mr. Mark Cramer, JD – Immediate Past Chair

General Al Gray, USMC (Ret), 29th Commandant – At-Large Member

LtGen Mark Faulkner, USMC (Ret) – At-Large Member

Col Grant Sparks, USMC (Ret) – At Large Member

Members

Mr. Tom DeSanctis

MGySgt Osceola Elliss, USMC (Ret)

Col Chuck Geiger, USMC (Ret)

Col Bruce Gombar, USMC (Ret)

LtCol Lynn “Kim” Kimball, USMC (Ret)

CWO4 Richard McIntosh, USMC (Ret)

CWO5 Lisa Potts, USMC (Ret)

Col John B. Sollis, USMC (Ret)

GySgt Forest Spencer, USMC (Ret)

Staff

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret), Chief Executive Officer

Ashley Danielson, VP of Development

SgtMaj Joe Houle, USMC (Ret), Operations and Artifacts Director

Richard Koeckert, Accounting Manager

Carolina Museum of the Marine is a nonprofit organization that is rigorously nonpartisan, independent and objective.