Front and Center Vol. 2 No 4 April 2023

FRONT AND CENTER

Vol. 2, No 4, April, 2023

Mission

Honoring the legacy of Carolina Marines and Sailors and inspiring future generations.

A Message from the CEO

Since March Madness just ended and UConn won the National Championship, I thought it worthwhile to share a great story about Jim Valvano who coached N.C. State University (my alma mater) to a National Championship in 1983.

Jim Valvano was known for that unshakeable—borderline irrational even—belief in himself and in his teams. In his coaching career. In his battle with cancer. In every aspect of life, he lived by a quote he heard when he was a young boy, “Every single day, in every walk of life, ordinary people accomplish extraordinary things!”

Valvano was, himself, an ordinary kid with ordinary parents from an ordinary town where he received an ordinary education. Still, he did extraordinary things in his life. Valvano wasn’t yet out of high school when he first told his dad he had decided what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. He was going to be a collegiate basketball coach, he told him. With that high schooler’s naivete, he said, “Dad, I’m going to win a National Championship.”

A few days after Jim told his dad about his plans for the future, his dad called him into his bedroom. “See that suitcase?” he asked, pointing to a suitcase in the corner of the room.

Confused, Jim replied, “Yeah, what’s that all about?” “I’m packed,” his dad explained. “When you play and win that National Championship I’m going to be there, my bags are already packed.” “My father,” Jim would later say in his legendary ESPY speech, “gave me the greatest gift anyone could give another person, he believed in me”.

In the same respect, this is the gift that all the supporters of Carolina Museum of the Marine have given to us….you believe in us and the importance of this mission. Thank you! We will not let you down and we will build a world-class Museum. Please read the rest of our Newsletter to see the great progress we are making.

Semper Fi,

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret)

Chief Executive Officer

Situation Report

6 April 2023 – All hands were on deck as CJMW Architecture, HICAPS (construction management), Ralph Appelbaum Associates (RAA exhibit designers), and Samet Corporation gathered in Jacksonville, NC to visit the site, review the 50% concept for exhibit designs, and discuss details of finishes and civil engineering.

Overarching principle: Semper Fidelis!

Pictured:

Upper left: Carl Schuemann, Samet Corporation; Matt Krupanski, RAA; CEO Kevin Stewart and Curator Lisa Potts, CMOTM | AGCI.

Upper right: Joe Houle, Director of Operations and Artifacts, CMOTM | AGCI; Mary Beth Byrne, RAA; Matt Krupanski, RAA; and Lisa Potts, Curator CMOTM | AGCI

Lower left: Dave Smith, HICAPS; Lisa Potts Curator, CMOTM | AGCI; Nick Appelbaum, RAA; Mary Beth Byrne, RAA; Kevin Stewart, CEO, CMOTM | AGCI; Joe Houle, Director of Operations and Artifacts, CMOTM | AGCI; John Drinkard, CJMW Architecture.

Off camera: Tom Calloway, CJMW Architecture; Matt Krupanski, RAA

We thank our friends at Sturgeon City Environmental Education Center, as always, for hosting our meeting! When you visit Jacksonville, NC, don’t miss the opportunity to check out this jewel in eastern North Carolina.

Interview with Carolina Marines and Sailors

Dr. Jim Danielson interviews

Col Tim Howard, USMC (Ret)

and SgtMaj Raquel Painter, USMC (Ret)

Al Gray Marine Leadership Forum Essays

The intent of these essays is to create public discourse and spur thought. In line with our mantra of “teaching how to think, not what to think” these essays are complex, and the issues addressed are difficult to navigate without sparking some disagreements.

We welcome this, as we work to inspire principled and committed leaders.

“Grow, Don’t Climb”

by James Danielson, PhD

USMC Veteran

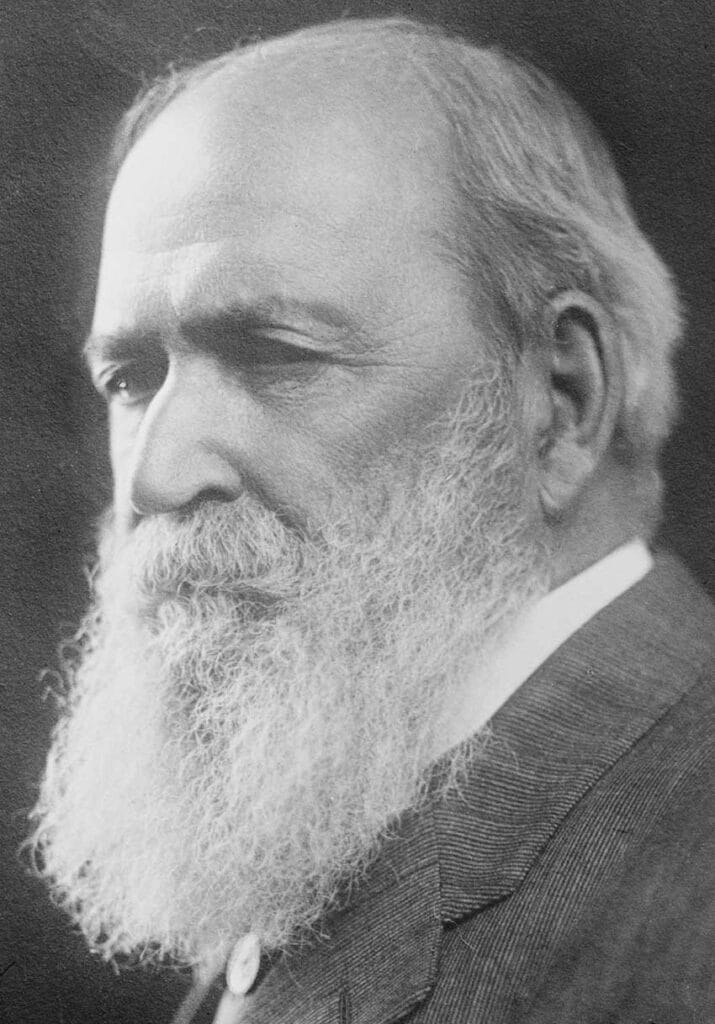

George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress)

Basil L. Gildersleeve was born October 23, 1831 in Charleston, South Carolina. He was among the first Americans to earn a German doctorate in Gottingen University. In 1856, Gildersleeve was appointed professor of Greek, and later of Latin, also, in the University of Virginia. During the war of 1861-65, Gildersleeve taught classes in the fall and spring terms in the University, and in the summer served in the army of the Confederate States of America, in which service he was severely wounded in battle. In 1876, Gildersleeve became one of the original five full professors in the newly founded Johns Hopkins University where he established a department of Greek and Roman literature. He retired from teaching in 1915, and died on January 9, 1924. Basil Gildersleeve is buried in the University of Virginia Cemetery in Charlottesville. During his lifetime, Gildersleeve was generally regarded as the finest scholar of classics in the United States, and a revered teacher who was concerned not just in the intellectual development of his students, but in their development as human beings. To that end, he often admonished students with these words: “Grow, don’t climb.”

“Esse Quam Videri.” To be rather than to seem.

Images from NC Department of the

Department of Secretary of State

Gildersleeve’s admonition is a natural fruit of the western intellectual tradition which he knew so well, and is echoed in the state motto of North Carolina: Esse quam videri, “To be, rather than to seem.” This motto captures well Gildersleeve’s advice to students that their first concern should be growth as human beings, rather than jostling and competing for position and status, which has its place in life, but not first place. How, then, may we think of the process of growing as a human being? We should observe at the beginning that human nature is moral and intellectual, and therefore the capacities of nature that are uniquely human, when developed well, constitute the moral and intellectual virtues.

We should also observe that human beings are social creatures by nature, that the first society we each encounter is the family, and that this fact demonstrates the importance to individual growth of a living cultural tradition in which human beings may flourish. Interestingly, in order for human beings truly to grow as human beings, they need a healthy and vibrant cultural tradition, but in order for a cultural tradition to be healthy and vibrant, there must be in it human beings possessed of moral and intellectual virtue. Plato captures this idea concisely when he writes that no society can be just without just people, and by this he meant people with well-ordered souls (psyche), or possessed of moral and intellectual virtue. What is virtue and how are virtues developed?

Plato and his illustrious student Aristotle agreed that the virtues are most readily acquired in childhood, and this is why education for the young primarily should be “training in the habits of goodness.” The argument is that from our earliest years, we human beings are developing habits and those habits can be good, virtue, or bad, vice. Someone who develops bad habits of conduct and mind, upon coming to the age of reason and understanding, will find it difficult to undo those habits and replace them with good ones, if he even comes to be aware of his condition, or cares about it. But when the young are trained in the habits of goodness from the beginning, when they come to the age of reason, they will understand why they were educated as they were, and thus be able to take over the supervision of their further growth and development.

Virtue may be understood as a habit by which the capacities of our nature are used for good and not for evil ends. This follows what is known as the first principle of practical reason: good should be done and pursued, and evil avoided. One might object that “good” and “evil” are disputed terms, and so this first principle has limited application. There is nothing that rises above the trivial that people won’t dispute, and the trivial is often the stage of controversy, so this objection is simply a recognition of the obvious. Moreover, we have within us a natural attraction to what is good for us, and a natural aversion to what is harmful or dangerous. In general, we can say that what attracts us is good, what repels us is evil.

When we are conceived, we receive all of the human nature we will ever have, but the capacities of our nature are in potential, needing to be actualized. It is just this that ancient Greek thinkers said should be the object a child’s upbringing and education, and it is this, moral and intellectual growth through actualizing the unrealized potentials of our nature, that produces the inner confidence and peace that are critical elements of happiness in life. Perhaps at this point, something should be said about what is meant by “moral.” The Canadian philosopher George Parkin Grant has observed that Canada and the United States are two countries in the western European tradition with no histories before the modern period. Of course, we have inherited a cultural tradition that is ancient, but when studying American history, teachers rarely draw the attention of students to that ancient past. So many Americans have been exposed, at best, only to modern approaches to thinking about morality and thus regard the word “moral” as identifying certain rules like don’t lie, cheat, or steal, keep your promises, be faithful in marriage, be honest in business, and so on. But in pre-modern European thought, moral philosophy was the study of human beings, that is, the consideration of what kind of beings we are, what is our nature, and thus what are the best kinds of life for beings like us to live. Aristotle would say that for human beings, the object is not simply to live, but to live well. By this, of course, he meant that integral to a life well lived is the development of the capacities of our nature into virtues. In other words, in pre-modern thought, the focus of morality, or ethics, is not on rules that can be followed even by people of low character, which rules allow us each to go his own way without interfering with others, but to become a good man or woman who does what is good by habit and so needn’t carry around a code of rules to follow.

There are many virtues, just as there are many points on a compass. The United States Marine Corps, for example, holds to the core values of honor, courage, and commitment. These are virtues, as are generosity, frugality, and patience. Like a compass, there are four virtues that are called “cardinal,” and the others take their various shades of meaning from these. The cardinal virtues are prudence, courage, temperance, and justice. Virtues have also corresponding vices. Prudence may be contrasted with imprudence, courage with cowardice, temperance with want of discipline in thought and action, justice with injustice (which characterize both individuals and societies).

A well-known source of writings in moral philosophy defines prudence this way. The virtue of prudence is “an intellectual habit enabling us to see in any given juncture of human affairs what is virtuous and what is not, and how to come at the one and avoid the other.” Prudence is an intellectual virtue in that it aims at orienting the intellect to truth, but it may be held also to be a moral virtue because it seeks truth in taking practical decisions for action.

In the development of the understanding of courage from Greece in the 4th century B.C. to Paris in the 13th century, we see it beginning as the martial virtue of the soldier in battle, standing firmly and with clarity of purpose in the midst of danger, and developing into a steady disposition of endurance under the demands of challenges of all kinds. The 13th century Dominican friar Thomas Aquinas argued not only that courage is endurance under hardships of any kind whatever, but that for this reason, courage is the steady expression of all of the virtues of the human soul because a virtuous person does not take holidays from the good to dabble in behaviors that might be fun or momentarily exciting but also morally corrupting. We have observed that we human beings have a natural appetite or desire for what is good, and a natural aversion for what is dangerous or harmful. Courage is the virtue that manages the urge for aversion so that one remains steady and focused in hardship. Temperance is the virtue that manages the appetite of desire.

Temperance is “the righteous habit which makes a man govern his natural appetite for pleasures of the senses in accordance with the norm prescribed by reason.” The pleasures of concern here fall into three classes: those associated with the preservation of the individual, those associated with the perpetuation of the human race, and those associated with the well-being and comfort of a human life. Thus we see three attendant and subordinate virtues in harmony with temperance: abstinence, chastity, and modesty. Abstinence functions in relation to food and drink and here one must follow the counsel of reason because temperance in food and drink will vary from one person to another. Men in general need more food than do women in general. Athletes will need more food and drink than retired office workers, and so on. Abstinence avoids the vices of gluttony and drunkenness. The function of chastity is to regulate one’s disposition toward the sensual satisfactions that attend sexual reproduction, that is, to avoid the excesses occasioned by the vice of lust. Modesty is the virtue by which we manage the human passions that lie in us less violently than do the passions for food and drink, and for sex. It expresses itself in us as a kind of humility by which one’s interior life is set in order (and contributes importantly to inner peace). Modesty regards such things as style of life, manner of speech and dress, how one carries himself, and the like, and this helps us understand why temperance is a cardinal virtue.

Justice is considered the most important of the cardinal virtues because it regulates our interactions with others. “It is a moral quality or habit which perfects the will and inclines it to render to each and to all what belongs to them.” The virtue of charity inclines us to assist others out of our own means. Justice requires us to give to others what belongs to them. This includes normal and accepted social courtesies and manners, keeping one’s agreements with others, keeping one’s word and promises, keeping one’s hands off of others without their permission, and keeping one’s hands off of other people’s property. It has long been understood that no society can be free that does not hold secure the property rights of individuals. When government takes to itself the authority to determine how much of a man’s property he may keep, liberty is at an end.

Americans of our founding generation understood the importance of virtue in the people to the maintenance of a free and well-governed society. Certainly, Americans of Basil Gildersleeve’s generation understood this, too. And of course, Gildersleeve himself understood the tradition of virtue ethics very well, and it gave rise to his admonition to “Grow, don’t climb.”

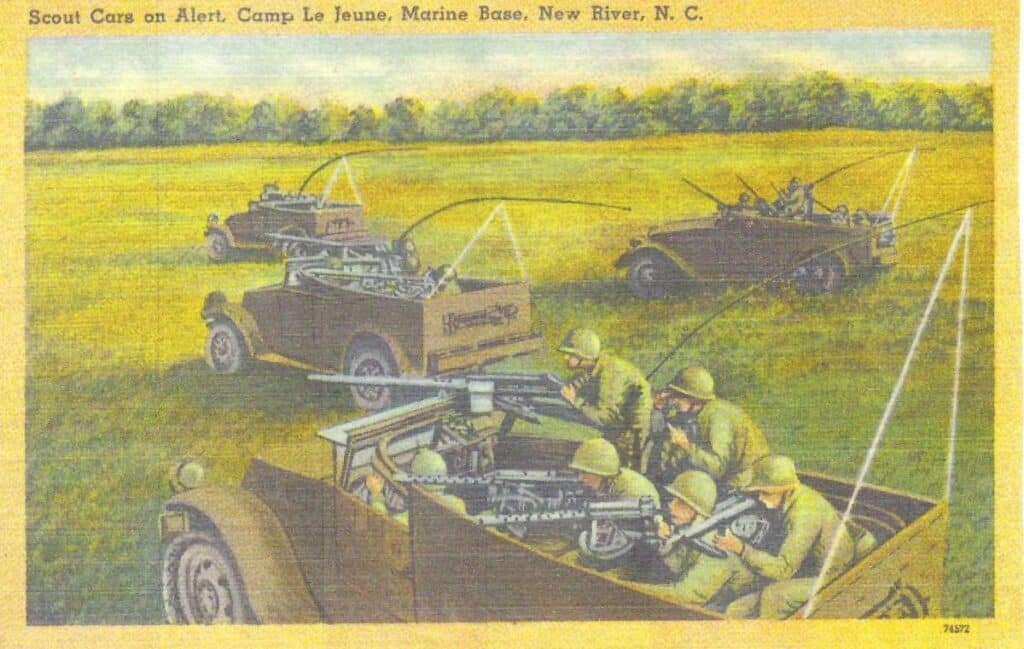

The Owens Halftrack

by LtCol L.J. Kimball, USMC (Ret)

On 16 May 2011, a beautifully restored 1942 M2 halftrack was generously donated by Gary Hedbing’s Halftrack Parts’ CEO Gary Hedbing and VP Curt Stodhill to the Carolina Museum of the Marine (CMOTM). This professionally done restoration, a four-year project, patriotically funded by Mr. Hebring at a cost of $38,413, was executed under the direction of Ron Leatherman of the Military Vehicle Repair and Restoration company substantially assisted by Tom Eagles of South Carolina’s North American Rescue Products, who was instrumental in facilitating the eventual donation. The most telling indicator of the quality of this restoration was its assessed value at the time of its transfer to the CMOTM, $190,000. Yet this masterfully done restoration serves more than as an exemplar for interpreting the role of the self-propelled gun by the Carolina Marines, it was also intended by its generous benefactors to be a memorial to a particular Carolina Marine, Sergeant Robert A. Owens.

The M2 was the middle sibling in a three-vehicle family of lightly armored vehicles designed by and produced primarily by the White Motor Company of Cleveland, OH. Germany’s rapid overrun of western Europe and its successful employment of mechanized infantry in conjunction with tanks and self-propelled artillery provided a forceful incentive for the U. S. Army to revitalize its stagnant armor formations in preparation for America’s seemly inevitable entry into the war. And, there appeared no better model to emulate than the German army. In addition to significantly upgrading its tanks, the Army needed a scouting vehicle, a prime mover for towed artillery and personnel carriers, all armored. Rapidly responding to requests from the U. S. Army Ordnance Department, American industry, initially the White Motor Company, complied in 1940 with the M3 (White) scout car and the M2 and M3 halftracks. All three were virtually identical in appearance, particularly the M2 and M3 halftracks, except that the scout car lacked the halftrack component underneath the rear of its hull. There was little more than a foot’s difference between the three in any dimension.

Universally adopted in all theaters of the war, thousands were required by the U.S. and its Allies although, surprisingly, with the rapid technological evolution characteristic of warfare, they were only produced for four years before being supplanted by more capable vehicles. Over 20,000 scout cars (M3) were produced and 53,000 halftracks (M2/M3) in 70 different versions, mostly with differing armament. They were considered mechanically reliable, easy to operate and relatively inexpensive using the same interchangeable parts, many from common commercial vehicles. Offroad performance was generally good, except for the scout car, the trafficability of which was limited by the lack of a halftrack component. Their short comings, however, were critical, the absence of overhead protection and thin armor, mostly only ¼-inch, that allowed penetration by machine gun rounds.

In the Pacific, the Marine Corps fought a different war than the U. S. Army did in Europe, as any student of the war well appreciates. This distinction greatly affected the use, numbers required and employment of the scout car and halftracks. The Japanese-held atolls and small islands to be assaulted didn’t anticipate confrontation with German mechanized units. Prior to April 1942, the Marine Corps, particularly the Carolina Marines’ 1st Marine Division (MarDiv), was contemplated as part of an amphibious force that might eventually conduct contested landings in Europe, and more immediately, to engage German or Axis forces under various contingency plans involving, for example, the Azores and Martinique. During April, the Joint Chiefs of Staff dictated that Marine divisions would be relegated to the Pacific, only Army divisions would operate in the Atlantic.

Scout cars no longer would be required to roam over expanded European beach heads and became orphan-like in the MarDiv organization until ignominiously replaced by the ¼-ton jeep. The M2 halftrack, which the Army envisioned as a prime mover for artillery, was eschewed in favor of the M3 halftrack, which was better configured as a personnel carrier, and for use as self-propelled artillery. The Marines did not develop an antitank doctrine during the war, but it was in that mission, and against fortifications, that the Corps found the greatest use for its M3s. Augmented by a mounted field gun, it became a M3 Self-Propelled Mount (SPM) or, more commonly, a Motor Gun Carriage (MGC). The weapon of choice, primarily because it was it was the one initially incorporated in the Army’s M3 MGCs and readily available from WW I surplus stocks, was the famous French 75 mm Model 1897 field gun, which was quite adequate against Japanese armor. MarDivs would have twelve M3 MGCs, initially six in the Special Weapons Battalion (SWB) and two in each Regimental Weapons Company (RWC). Prior to the Marshalls Islands’ campaign, and the deactivation of the SWBs, all twelve were transferred to the RWCs.

Carolina Marine M3 MGCs saw action on Guadalcanal, Tarawa Saipan and Tinian during WW II. Although they were undoubtedly used effectively in general support throughout the campaigns, there are only four instances where they were specifically mentioned in direct action. On 23 October 1942, fire from a M3 GMC helped defeat an attack by the Japanese Sendai Division against the 1st Marines at the mouth of the Mantanikau River on Guadalcanal. (The 1st MarDiv was still considered “Carolina Marines” until after Guadalcanal.) On Tarawa (D+1), 21 November 1943, the situation was still in doubt on the landing beaches and Col. David Shoup had to call for the landing of the MGCs to supplant the ineffective Sherman tanks supporting the 2nd MarDiv. On Saipan, 16 June 1944, M3 GMCs helped annihilate a 44-tank Japanese counterattack against the 6th Marines in what would be the largest tank action of the war. On Tinian, 30 July 1944, MGCs are specifically mentioned in reducing Japanese strong points as the 2nd MarDiv advanced northward.

Tinian was the last employment of M3 GMCs by the Carolina Marines. Following Iwo Jima, Corps-wide, the M3 GMCs were replaced in the RWCs by M7 GMCs with their upgraded 105 mm howitzers. M7 MGCs were with the 2nd MarDiv on Okinawa but, along with the division, were not significantly engaged.

Sgt Owens was a South Carolina boy, born in Greenville on 13 September 1920. Eventually moving to Spartanburg, his SC residence was a strong motivating factor in Mr. Eagles personalizing the track to his memory, as can be seen in the attached photo of the subject M2. Regarding the vehicles’ fictitious number “8313920” for example, the “8” realistically identifies it as a Marine Corps halftrack, the “3” as belonging to the 3rd MarDiv, but the remainder is Sgt Owens’ serial number. The diamond-shaped tactical marking containing the numbers “3-3-1” on the hull next to the self-explanatory image of the Medal of Honor establishes, as it is portrayed, it’s actual service history being unknown, that it belonged to the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, 3rd MarDiv, as did Owens on Bougainville. The Marine Corps did not operate the M2 so it must be remembered that this vehicle is intended to be a memorial, and is decorated as such, not as a literal, inerrant portrayal of a specific historic vehicle although its configuration is historically accurate. It is as much a monument to the Corps’ M3 as it is to Sgt Owens.

Answering his country’s call after Pearl Harbor, Owens enlisted in the Marine Corps on 10 February 1942, received his recruit training at Parris Island, then reported to the 1st Training Battalion of the 1st MarDiv at Marine Barracks, New River, subsequently Camp Lejeune, for further infantry training. When the 3rd Marines were activated there on 16 June as a separate reinforced regiment from the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Training Battalions, his unit was redesignated as Company A, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines. As a separate regiment, still with a Camp Lejeune birthright, the 3rd Marines were deployed to American Samoa and attached to the 2nd Marine Brigade for additional training, finally joining the 3rd MarDiv after its activation on 16 September. He was a Carolinian by birth and had been a Carolina Marine for 17 months.

The 3rd MarDiv echeloned into New Zealand between January and March 1943, was redeployed to Guadalcanal by August, and on 1 November joined the Bougainville campaign with an amphibious assault at Cape Torokina, where Sgt Owens heroic actions placed him firmly in the pantheon of legendary Marines and garnered him the award of the Medal of Honor. His citation read in part:

CITATION: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty …in action against enemy Japanese forces during extremely hazardous landing operations at Cape Torokina on 1 November 1943. Forced to pass within disastrous range of a strongly protected Japanese 75-mm gun strategically located on the beach, our landing units were suffering heavy losses…and the success of the operation was seriously threatened. Observing the ineffectiveness of Marine attacks against the devasting fire of the enemy weapon and aware of the need for prompt action, Sgt Owen unhesitatingly charged the gun bunker and steadily firing cannon from the front, calling on four of his comrades to assist in placing covering fire on two adjacent bunkers. Entering the emplacement through the firing port, he drove out and killed the gun crew before he himself was wounded. Indominable and aggressive in the face of almost certain death, Sgt Owen silenced a powerful gun that was of inestimable value to the Japanese defense and by his initiative and spirit of self-sacrifice, contributed immeasurably to the success of the landing operation. His valiant conduct throughout reflects the highest credit upon himself and the U. S. Naval Service.

What is not stated in the citation is that by his heroic and successful clearing of the gun bunker, he had further exposed himself to the Japanese defenses and a grenade thrown from an adjacent bunker took his life. Major General Allen H. Turnage, Commanding General of the 3rd MarDiv, further commented: “Among many brave acts on the beachhead of Bougainville, no other single act saved the lives of more of his comrades or served to contribute to the success of the landings.” There is little doubt that Sgt Owens fully merited the Medal of Honor as well as the further memorialization of his service in the restoration of the “Sgt Robert A. Owens” M2 halftrack.

As a final footnote, on 22 July 1946 the Gearing-class destroyer USS Robert A. Owens (DD-827) was christened at Bath, Maine, in his honor.

NOTE: The M2 Halftrack is in use by Carolina Museum of the Marine as an invaluable and popular addition to community events.

M2 HALFTRACK SPECIFICATIONS (Standard, unmodified)

DIMENSIONS: Length-19’7”, Width-7’3”, Height-7’5”

WEIGHT: 18,000 lbs

ENGINE: 386 cu in White 160AX inline six gasoline engine, rated at 148 hp

MAX SPEED: 45 mph

RANGE: 220 miles

ARMOR: 1/4-1/2 in

The standard, unmodified versions of the M3 scout car and the M2/M3 halftracks were all initially armed with a combination of three machine guns, usually two M1919 A4 .30 cal and one M2 HB .50 cal, all mounted on a skate rail mounted inside the hull.

REFERENCES

Col Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret). Across the Reef: The Marine Assault on Tarawa. Marines in WW II Commemorative Series. Washington: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1993.

The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa. Marines in WW II Commemorative Series. Washington: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1996.

Capt John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret). Breaching the Marianas: The Battle for Saipan. Marines in WW II Commemorative Series. Washington: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1994.

Kenneth W. Estes. Marines Under Armor: The Marine Corps and the Armored Fighting Vehicle, 1916-2000. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2000.

Richard Harwood. A Close Encounter: The Marine Landing at Tinian. Marines in WW II Commemorative Series. Washington: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1994.

Ian V. Hogg, introduction. The American Arsenal. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2001.

Sgt Robert A. Owens award citation. RefSec, MCHC, Washington, D.C.

Gordon L. Rottman. U. S. Marine Corps WW II Order of Battle: Ground and Air Units in the Pacific War. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002.

Henry I. Shaw, Jr. First Offensive: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal. Marines in WW II Commemorative Series. Washington: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1992.

Steven J. Zaloga. M3 Infantry Half-Track 1940-1973. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1994.

Numerous unpublished letters, invoices and other documents between Gary Hedbing, Ron Leatherman and Tom Eagles, 2007-2011. In possession of the CMOTM.

Thank you to our generous friends at Texas Roadhouse – and for all of the hungry supporters who turned out to support us in March!

Marines Making News…

Visit Marines.mil for up-to-date information about United States Marines who are making news.

Please join us in supporting the mission of

Carolina Museum of the Marine

When you give to our annual campaign, you help to ensure that operations continue during construction and when the doors open!

Stand with us

as we stand up the Museum!

Copyright April, 2023

Carolina Museum of the Marine

2022-2023 Board of Directors

Executive Committee

LtGen Gary S. McKissock, USMC (Ret) – Chair

Col Bob Love, USMC (Ret) – Vice Chair

CAPT Pat Alford, USN (Ret) – Treasurer

Col Joe Atkins, USAF (Ret) – Secretary

Mr. Mark Cramer, JD – Immediate Past Chair

General Al Gray, USMC (Ret), 29th Commandant – At-Large Member

LtGen Mark Faulkner, USMC (Ret) – At-Large Member

Col Grant Sparks, USMC (Ret) – At Large Member

Members

Mr. Keith Byrd, US Marine Corps Veteran

Mr. Tom DeSanctis

MGySgt Osceola Elliss, USMC (Ret)

Col Chuck Geiger, USMC (Ret)

Col Bruce Gombar, USMC (Ret)

LtCol Lynn “Kim” Kimball, USMC (Ret)

CWO4 Richard McIntosh, USMC (Ret)

CWO5 Lisa Potts, USMC (Ret)

Col John B. Sollis, USMC (Ret)

GySgt Forest Spencer, USMC (Ret)

Staff

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret), Chief Executive Officer

Ashley Danielson, VP of Development

SgtMaj Joe Houle, USMC (Ret), Operations and Artifacts Director

Richard Koeckert, Accounting Manager

Carolina Museum of the Marine is a nonprofit organization that is rigorously nonpartisan, independent and objective.