The Battle Of New River

Onslow County, by November 1862, found herself on the frontiers of the Confederacy with the White Oak River separating the Union Forces operating out of enclaves in and around New Bern to the north and the Confederates headquartered at Wilmington to the south. Offshore, the Windswept ships of the blockading squadron ranged up and down the coast. Onslow’s most storied Civil War engagement took place during this month when the Union gunboat Ellis under the irrepressible Lieutenant William B. Cushing ventured up the New River, occupied the county seat of Jacksonville, and fought encircling rebel forces over the next two days in attempting to escape.

The signal events of this engagement took place in Camp Lejeune’s contiguous waters and in and adjacent to the land area that became the base. The significance of the engagement is clearly evidenced by its commemoration in Onslow County’s only Civil War related NC state historical marker, a NC Civil War Trails marker, and in one of the 14 Camp Lejeune base historical markers.

Lieutenant Cushing, the youngest commander of a U.S. vessel of war, absolutely fearless, and already an implacable foe of secession, edged the Ellis cautiously into the New River on the 23rd. His mission was to raid Jacksonville and destroy any shipping or saltworks found on the river. The yellow fever epidemic in Wilmington and the presence of the blockade off the Cape Fear River had made the New River an attractive option to southern intracoastal commerce.

Despite the efforts of pickets racing up both sides of the river and causing a schooner to be burned in route, Cushing surprised the drowsing postal village at one o’clock and threw a landing party ashore. Mindful of the proximity of roving Confederate units, he ceremoniously ran up the U. S. flag at the courthouse and reembarked by two-thirty. With him went a quantity of captured arms, clothing, mail, other contraband and two schooners.

The southern forces operating in the area, Companies A and B of the 2nd N.C. Cavalry, were now fully aroused and converging on the river. By themselves there was little they could do but harass the gunboat with small arms fire. Encumbered by the trailing schooners, however, Cushing was unable to reach the river’s mouth before nightfall compelled him to anchor in midstream, just offshore from the then existing community of Marines, now Courthouse Bay. This unplanned delay gave the rebels the chance they needed to substantially improve their capabilities against the iron-hulled Union steamer.

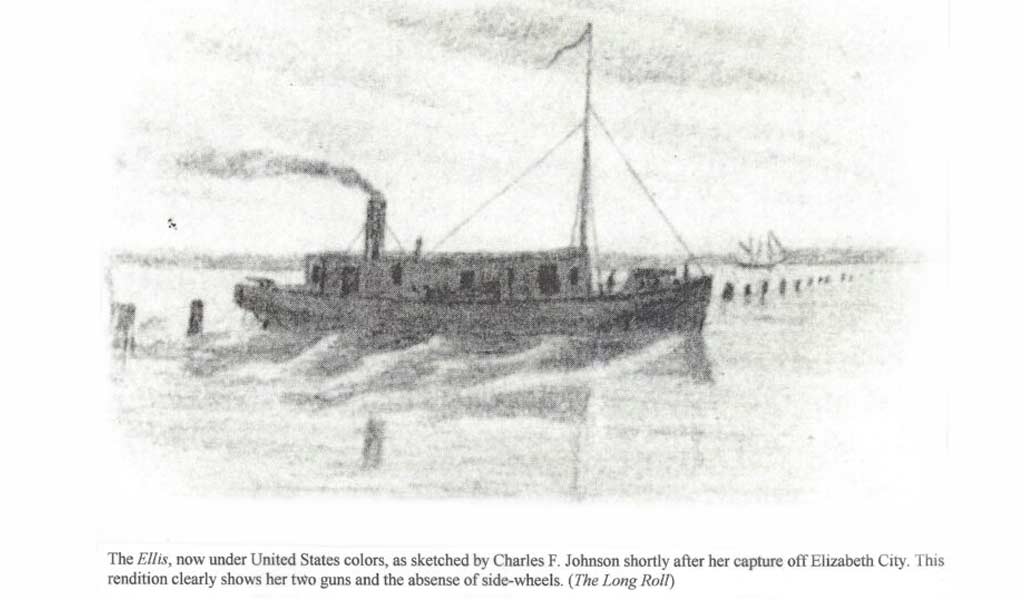

Galloping up the road from Wilmington came a section of howitzers from Company G of the 2nd N.C. Artillery, which was occupying a fortified line north of the city at Sloop Point. By daybreak on the 24th, they had established an ambush on the western side of the river between Hatch’s and Swan’s Points where the channel passed within one hundred yards of a tree-lined bluff. From here the masked battery and Company A could riddle the slowly moving gunboat at point-blank range. The Ellis’s superior firepower, a 6.4-inch rifled gun mounted forward and a 12-pounder howitzer aft, would be of little benefit with the gun crews swept from the deck by the hidden riflemen.

Confederate fortunes swung both ways that brisk November morning as the Ellis got underway and headed expectantly for the New River inlet. First, the concealed marksmen inadvertently opened up prematurely on the descending steamer before she entered the targeted channel. The unimpeded gunboat swung easily away from the bluff and blasted the tree line at will from a safer distance, forcing the Confederates to hastily withdraw. Then, entering the channel, she carefully proceeded down its length without further opposition. With the inlet in sight, the Ellis exited the channel, increased speed, turned slowly to the left, and ran hard aground quite unexpectedly on a hidden shoal.

All efforts failed to refloat the stranded vessel. As autumnal darkness again approached, Cushing sent a small landing party ashore, with considerable misplaced confidence, to capture the rebel artillery, which fortunately for the tars had withdrawn and not yet returned, but they did manage to wreck a salt works. He then transferred everything to one of the captured schooners except himself, six volunteers, and the 6.4-inch pivot gun, which at 8000 pounds in weight was completely unmanageable, and sent the schooner out of range. His intention was to fight the Ellis until the morning tide freed them. If that failed, there was always the ship’s boat for escape; surrender was unthinkable. Meanwhile, further Confederate reinforcements hurried up the Wilmington Road, the remainder of Company G and a hull-busting Whitworth 12-pounder rifle.

As the immobile Ellis became visible on the 25th, the rebel artillery commenced a devastating fire from four positions on the river bank, barely five hundred yards away. Cushing’s small crew was soon overwhelmed. Realizing the inevitable, he set her afire to prevent capture and joined his tars in the ship’s boat to race the southerners to the schooner and out the inlet. It was a near thing. The exploding Ellis discouraged any pursuit from the shore by small boat and the hard riding cavalrymen managed just to reach the inlet as Cushing and his schooner broke through the last line of breakers and into the Atlantic.

Both sides claimed victory in the engagement. Cushing received commendation, promotion and went on to greater glory. His greatest fame would come in 1864 with the daring destruction of the formidable Confederate ram, the Albemarle; hence his sobriquet “Albemarle Cushing” that followed him the remainder of his storied career. Upon his untimely death in 1874 he was proclaimed by Admiral David Farragut to have been “the hero of the war.” The Ellis rusted in solitude in the shallows of the New River until claimed by a salvage crew in 1867 and towed to Wilmington. Following this much celebrated engagement, Onslow continued as a minor battleground for the remainder of the war, serving at its end as a route of march for part of the Union forces converging on Joseph E. Johnston’s overmatched army.

Selected References

William Barker Cushing. “Outline Story of the War Experiences of William Barker Cushing, As Told by Himself.” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, 1912.

E.M.H. Edwards. Commander William Barker Cushing of the U.S. Navy. London: Neely, 1896.

LtCol Frederick W. Hopkins, USMCR. “The Battle of New River.” Unpublished manuscript, ca. 1942. MCB Camp Lejeune Historical Reading Room.

“Important from North Carolina: A Brilliant Fight Near the Mouth of the New River Between the Gunboat Ellis and a Rebel Battery.” New York Herald, 4 Dec 1862.

Ralph J. Roske and Charles Van Doren. Lincoln’s Commando: The Biography of Cdr. William B. Cushing, USN. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1957.

R. N. Scott, et. al. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 128 vols. Ser. I, vol. 8. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1891.

Franklin W. Smallman. The Smallman Collection. Correspondence and notes of Franklin W. Smallman, naval historian. In possession of author.

Posted on: September 28, 2021