Front and Center Newsletter – Vol. 3, No. 7, July 2024

Under Construction!

Mission

Honor, preserve, and teach the legacy of Carolina Marines and Sailors.

Showcase the Marine example to inspire future generations.

.

Message from the CE0

Dear Marines and Sailors, Friends and Family,

It is an exciting time for the Carolina Museum of the Marine. After a superb groundbreaking ceremony, our general contractor (SAMET) has been getting to work and starting the actual construction. Construction fencing is up, and the ground is being prepared….it is happening, and we are on our way to delivering a world-class Museum that all will be proud of.

Additionally, we have been working with our exhibit designers (Ralph Applebaum Associates) to finalize the exhibit design. Everything is coming together nicely, and we will be able to share new renderings very soon.

There is still much to do and the coordination with all the stakeholders is a complex undertaking, so your continued support is critical during this phase of the project. Thank you!

Also, thank you for all those that supported or participated in our inaugural Al Gray, Marine Golf Tournament….it was a successful event, and we could not have done it without you

Lastly, have a great July 4th!

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret)

Chief Executive Officer

Click here for ongoing construction updates

Hard hats for everyone! Pictured above, right to left: Curator Lisa Potts, Exhibit Design team members from RAA, Lily Remmert and Laura Gunther, and CEO Kevin Stewart. Many thanks also to Matt Krupanski and Mary Beth Byrne, also of RAA, for presentation of 100% exhibit Design and Development while visiting Jacksonville!

Marine Corps Traits and Principles of Leadership, Part VII

by James Danielson, PhD

Marine Veteran

Upon hearing the Marine leadership principle of making sound and timely decisions, one might reasonably respond, “Right, but how?” We get a sense of how to understand what it means to take decisions that are “sound” from the description of this principle, and we find, interestingly, that demonstrating this leadership principle seems to be rather a consequence of particular traits of character.

_”Marines must be able to think and make quality decisions under pressure. Sadly, these decisions (or lack of initiative) can lead to the loss of life or other forms of devastation. Therefore, Marines as leaders must be able not only to make decisions but live with the consequences. Marines who understand the core leadership principles and values of the USMC are great improvisers. They are able to react and respond to unforeseen events and find solutions. Leaders know that things rarely go to plan, especially in the military where being able to adapt and remain flexible is imperative. Marines that can estimate a situation, along with the plausible outcomes, and then make a sound decision, make good leaders.”

A cursory reading of this description might leave one thinking there isn’t much here since we don’t find a dictionary definition of a sound decision. However, we get hints when reading that a leader must be able both to take decisions and to live with the consequences, that a leader must be able to respond to situations that have arisen unforeseen, in other words to be flexible and able to adapt, and importantly, a leader must be able to estimate, or evaluate a situation in order to decide the best way to respond. And of course, this must be done consistently.

It is one thing to understand the definition or description of a principle of conduct. It is something else to put the principle into action in one’s behavior. The practice of acting according to principle requires that one understands the importance of following principles that guide action and that one do so with attention and care, that is, with discipline. For centuries, moral philosophers have understood that when people guide their conduct according to proven principles of right behavior, they develop habits of action by which they demonstrate principles in action without having consciously to think about them. These habits traditionally have been called virtues and have long been thought to be important elements in lives well lived.

Leaders must be able to live with the consequences of their decisions. This involves having right intentions, which is an aspect of honor. In the 13th century, Dominican philosopher Thomas Aquinas argued that in order to be able accurately to evaluate the morality of an act, one must know three things: the act itself, the circumstances in which the act was performed, and the intention of the actor. This is seen, for example, in the distinction between sincerely being in error and lying. If one believes that what he is saying is true when it isn’t, he’s mistaken, but when he knows what he is saying is not true, then his intention is to deceive. That fellow is lying. Toward the end of the American Declaration of Independence we read in part: “We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions,…” Having right intentions is central to a clear conscience which in turn is fundamental to accepting and living with the consequences of our actions.

Right intentions are important, but we must be aware also of other traits of character that are needed by a conscientious leader like judgment, justice, decisiveness, integrity (by which right intentions are the only kind acceptable), dependability, and initiative. Such a leader will seek ever better to know himself and to pursue self-improvement, and will develop his skills, which may be called technical and tactical proficiency, will know his people and keep them informed, and in this way, set the example. For we humans, the possibility of making a mistake is ever present and we are prudent to keep this in mind. If, however, one is conscientious and disciplined, seeking to understand himself and develop into an ever-better human being, seeking also to be the best he can be at all aspects of his work, and possessed always of right intention, then should such a leader make a mistake, he is well-placed to be able to understand and to live with the consequences, and this is one place where courage and commitment are demonstrated.

The leadership trait of endurance is understood to be the ability to work consistently under challenging circumstances, and especially, over time. Ways of improving endurance include exercise to improve strength and stamina, maintaining healthy daily routines, and seeing challenges as opportunities to learn and to grow.

The Cambridge English Dictionary describes endurance as the ability to do things that are difficult, unpleasant, or painful over time. We might think of the capacity for tolerating necessary unpleasantness. When we consider the possibility of suffering when not in physical pain, endurance may be required when challenges are intellectual or emotional without involving physical danger. Yet we normally think of endurance as a quality of physical strength. Marines train for war, and in this training, physical conditioning and strength are important. Marines are also men and women, like the rest of our countrymen, and here also, among the populace in general, physical strength and good conditioning are important. We have presently in our society a problem with people suffering from poor conditioning and excess weight. Here, as elsewhere in life, the principles and traits of Marine Corps leadership, when practiced, make people better at being human, and therefore improve life.

Read more…

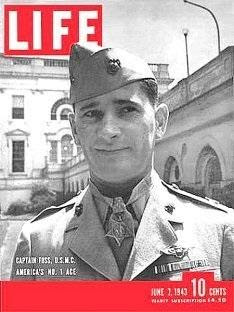

“Ace of Aces,” Joe Foss

Captain Joe Foss, USMC, was a fighter pilot at Guadalcanal during WWII. Within five months of arriving at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, Foss had shot down 26 Japanese fighter planes and bombers, tying the record of WWI ace Eddie Rickenbacker and earning the moniker “Ace of Aces.” Foss returned to the United States in March 1943, and on May 18, 1943, received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin Roosevelt. Foss’s Medal of Honor citation captures written accounts of his time at Guadalcanal.

Image: UNITED STATES 01.11.1943 Photo by Katie Lange DMA Social Media

For outstanding heroism and courage above and beyond the call of duty as executive officer of Marine Fighting Squadron 121, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, at Guadalcanal. Engaging in almost daily combat with the enemy from 9 October to 19 November 1942, Capt. Foss personally shot down 23 Japanese planes and damaged others so severely that their destruction was extremely probable. In addition, during this period, he successfully led a large number of escort missions, skillfully covering reconnaissance, bombing, and photographic planes as well as surface craft. On 15 January 1943, he added three more enemy planes to his already brilliant successes for a record of aerial combat achievement unsurpassed in this war. Boldly searching out an approaching enemy force on 25 January, Capt. Foss led his eight F4F Marine planes and four Army P-38s into action and, undaunted by tremendously superior numbers, intercepted and struck with such force that four Japanese fighters were shot down and the bombers were turned back without releasing a single bomb. His remarkable flying skill, inspiring leadership, and indominable fighting spirit were distinctive factors in the defense of strategic American positions on Guadalcanal.

Foss and his air group, called the “Cactus Air Force,” arrived at Guadalcanal on 9 October 1942. In his first combat mission, 13 October, Foss shot down a Japanese Zero, but his plane was damaged in the fight and with a dead engine in his aircraft, Foss landed at Henderson Field at full speed, no flaps, barely missing a stand of palm trees. On 7 November, Foss was shot down over the Pacific, surviving many hours in the water. He was rescued by a Marine in a large canoe manned by several natives of a nearby island, surviving his time in the water because of his Mae West life preserver, since the native of South Dakota couldn’t swim. During roughly three months of aerial combat, Foss and his squadron, known as “Foss’s Flying Circus,” shot down 72 Japanese aircraft, 26 of which were shot down by Foss himself, including the Japanese flying ace Kaname Harada, who Foss met after the war.

Foss and his air group, called the “Cactus Air Force,” arrived at Guadalcanal on 9 October 1942. In his first combat mission, 13 October, Foss shot down a Japanese Zero, but his plane was damaged in the fight and with a dead engine in his aircraft, Foss landed at Henderson Field at full speed, no flaps, barely missing a stand of palm trees. On 7 November, Foss was shot down over the Pacific, surviving many hours in the water. He was rescued by a Marine in a large canoe manned by several natives of a nearby island, surviving his time in the water because of his Mae West life preserver, since the native of South Dakota couldn’t swim. During roughly three months of aerial combat, Foss and his squadron, known as “Foss’s Flying Circus,” shot down 72 Japanese aircraft, 26 of which were shot down by Foss himself, including the Japanese flying ace Kaname Harada, who Foss met after the war.

Following military service, Foss returned to his native South Dakota where he served several terms in the South Dakota House of Representatives. His performance there, and his fame as an American war hero, put him in position to become governor of South Dakota, serving two terms in that office. (Interestingly, Foss lost a run for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives to fellow pilot George McGovern.) After leaving the governor’s office, Foss became the first commissioner of the American Football League. Foss worked to expand the league, making important television deals with ABC in 1960 to broadcast AFL games for $10.6 over five years, and in 1965, a 36 million-dollar contract with NBC for five years. For several years, including his time as AFL commissioner, Foss hosted a hunting and fishing program on ABC called The American Sportsman. In 1988, Foss served two consecutive one-year terms as president of the National Rifle Association.

Joe Foss died at 87 on January 1, 2003 in Scottsdale Arizona due to complications from a stroke suffered the previous October. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

General Al Gray’s 95th birthday guests stopped by to talk about their experiences with the 29th Commandant over his many years of service to this nation. We continue this series in honor and memory of Al Gray, Marine.

Beirut veteran, GySgt Dan Joy, USMC (Ret) was among those who attended.

(See all of the interviews celebrating General Gray and his legacy at

General Al Gray’s 95th Birthday.)

Please join us in supporting the mission of

Carolina Museum of the Marine.

When you give to our annual campaign, you help to ensure that operations continue during construction and when the doors open!

Stand with us

as we stand up the Museum!

Copyright July 2024. Carolina Museum of the Marine

2023-2024 Board of Directors

Executive Committee

LtGen Mark Faulkner, USMC (Ret) – Chair

Col Bob Love, USMC (Ret) – Vice Chair

CAPT Pat Alford, USN (Ret) – Treasurer

Mr. Mark Cramer, JD – Secretary

In Memoriam: General Al Gray, USMC (Ret)

MajGen Jim Kessler, USMC (Ret)

Col Grant Sparks, USMC (Ret)

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret), CEO, Ex Officio Board Member

Members

Col Joe Atkins, USAF (Ret)

Mr. Mike Bogdahn, US Marine Corps Veteran

Mr. Keith Byrd, US Marine Corps Veteran

MGySgt Osceola “Oats” Elliss, USMC (Ret)

Mr. Frank Guidara, US Army Veteran

Col Chuck Geiger, USMC (Ret)

Col Bruce Gombar, USMC (Ret)

LtCol Lynn “Kim” Kimball, USMC (Ret)

CWO4 Richard McIntosh, USMC (Ret)

The Honorable Robert Sander, Former General Counsel of the Navy

LtGen Gary S. McKissock, USMC (Ret)

Col John B. Sollis, USMC (Ret)

GySgt Forest Spencer, USMC (Ret)

Staff

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret), Chief Executive Officer

Ashley Danielson, Civilian, VP of Development

SgtMaj Steven Lunsford, USMC (Ret), Operations Director

CWO5 Lisa Potts, USMC (Ret). Curator