Grow, Don’t Climb

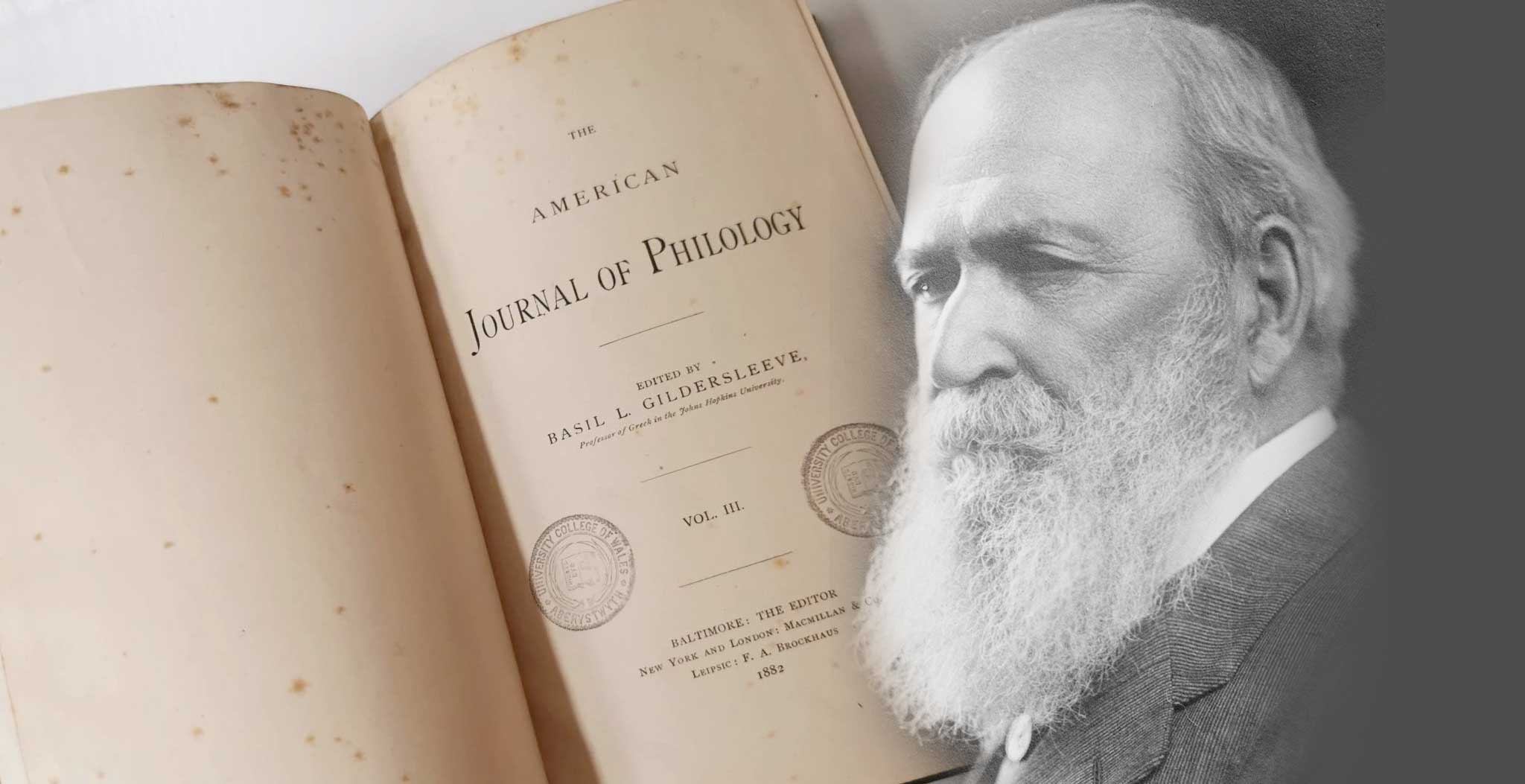

Basil L. Gildersleeve was born October 23, 1831 in Charleston, South Carolina. He was among the first Americans to earn a German doctorate in Gottingen University. In 1856, Gildersleeve was appointed professor of Greek, and later of Latin, also, in the University of Virginia. During the war of 1861-65, Gildersleeve taught classes in the fall and spring terms in the University, and in the summer served in the army of the Confederate States of America, in which service he was severely wounded in battle. In 1876, Gildersleeve became one of the original five full professors in the newly founded Johns Hopkins University where he established a department of Greek and Roman literature. He retired from teaching in 1915, and died on January 9, 1924. Basil Gildersleeve is buried in the University of Virginia Cemetery in Charlottesville. During his lifetime, Gildersleeve was generally regarded as the finest scholar of classics in the United States, and a revered teacher who was concerned not just in the intellectual development of his students, but in their development as human beings. To that end, he often admonished students with these words: “Grow, don’t climb.”

“Esse Quam Videri.” To be rather than to seem.

Images from NC Department of the

Department of Secretary of State

Gildersleeve’s admonition is a natural fruit of the western intellectual tradition which he knew so well, and is echoed in the state motto of North Carolina: Esse quam videri, “To be, rather than to seem.” This motto captures well Gildersleeve’s advice to students that their first concern should be growth as human beings, rather than jostling and competing for position and status, which has its place in life, but not first place. How, then, may we think of the process of growing as a human being? We should observe at the beginning that human nature is moral and intellectual, and therefore the capacities of nature that are uniquely human, when developed well, constitute the moral and intellectual virtues.

Gildersleeve’s admonition is a natural fruit of the western intellectual tradition which he knew so well, and is echoed in the state motto of North Carolina: Esse quam videri, “To be, rather than to seem.” This motto captures well Gildersleeve’s advice to students that their first concern should be growth as human beings, rather than jostling and competing for position and status, which has its place in life, but not first place. How, then, may we think of the process of growing as a human being? We should observe at the beginning that human nature is moral and intellectual, and therefore the capacities of nature that are uniquely human, when developed well, constitute the moral and intellectual virtues. We should observe also that human beings are social creatures by nature, that the first society we each encounter is the family, and that this fact demonstrates the importance to individual growth of a living cultural tradition in which human beings may flourish. Interestingly, in order for human beings truly to grow as human beings, they need a healthy and vibrant cultural tradition, but in order for a cultural tradition to be healthy and vibrant, there must be in it human beings possessed of moral and intellectual virtue. Plato captures this idea concisely when he writes that no society can be just without just people, and by this he meant people with well-ordered souls (psyche), or possessed of moral and intellectual virtue. What is virtue and how are virtues developed?

Plato and his illustrious student Aristotle agreed that the virtues are most readily acquired in childhood, and this is why education for the young primarily should be “training in the habits of goodness.” The argument is that from our earliest years, we human beings are developing habits and those habits can be good, virtue, or bad, vice. Someone who develops bad habits of conduct and mind, upon coming to the age of reason and understanding, will find it difficult to undo those habits and replace them with good ones, if he even comes to be aware of his condition, or cares about it. But when the young are trained in the habits of goodness from the beginning, when they come to the age of reason, they will understand why they were educated as they were, and thus be able to take over the supervision of their further growth and development.

Virtue may be understood as a habit by which the capacities of our nature are used for good and not for evil ends. This follows what is known as the first principle of practical reason: good should be done and pursued, and evil avoided. One might object that “good” and “evil” are disputed terms, and so this first principle has limited application. There is nothing that rises above the trivial that people won’t dispute, and the trivial is often the stage of controversy, so this objection is simply a recognition of the obvious. Moreover, we have within us a natural attraction to what is good for us, and a natural aversion to what is harmful or dangerous. In general, we can say that what attracts us is good, what repels us is evil.

When we are conceived, we receive all of the human nature we will ever have, but the capacities of our nature are in potential, needing to be actualized. It is just this that ancient Greek thinkers said should be the object a child’s upbringing and education, and it is this, moral and intellectual growth through actualizing the unrealized potentials of our nature, that produces the inner confidence and peace that are critical elements of happiness in life. Perhaps at this point, something should be said about what is meant by “moral.” The Canadian philosopher George Parkin Grant has observed that Canada and the United States are two countries in the western European tradition with no histories before the modern period. Of course, we have inherited a cultural tradition that is ancient, but when studying American history, teachers rarely draw the attention of students to that ancient past. So many Americans have been exposed, at best, only to modern approaches to thinking about morality and thus regard the word “moral” as identifying certain rules like don’t lie, cheat, or steal, keep your promises, be faithful in marriage, be honest in business, and so on. But in pre-modern European thought, moral philosophy was the study of human beings, that is, the consideration of what kind of beings we are, what is our nature, and thus what are the best kinds of life for beings like us to live. Aristotle would say that for human beings, the object is not simply to live, but to live well. By this, of course, he meant that integral to a life well lived is the development of the capacities of our nature into virtues. In other words, in pre-modern thought, the focus of morality, or ethics, is not on rules that can be followed even by people of low character, which rules allow us each to go his own way without interfering with others, but to become a good man or woman who does what is good by habit and so needn’t carry around a code of rules to follow.

There are many virtues, just as there are many points on a compass. The United States Marine Corps, for example, holds to the core values of honor, courage, and commitment. These are virtues, as are generosity, frugality, and patience. Like a compass, there are four virtues that are called “cardinal,” and the others take their various shades of meaning from these. The cardinal virtues are prudence, courage, temperance, and justice. Virtues have also corresponding vices. Prudence may be contrasted with imprudence, courage with cowardice, temperance with want of discipline in thought and action, justice with injustice (which characterize both individuals and societies).

A well-known source of writings in moral philosophy defines prudence this way. The virtue of prudence is “an intellectual habit enabling us to see in any given juncture of human affairs what is virtuous and what is not, and how to come at the one and avoid the other.” Prudence is an intellectual virtue in that it aims at orienting the intellect to truth, but it may be held also to be a moral virtue because it seeks truth in taking practical decisions for action.

In the development of the understanding of courage from Greece in the 4th century B.C. to Paris in the 13th century, we see it beginning as the martial virtue of the soldier in battle, standing firmly and with clarity of purpose in the midst of danger, and developing into a steady disposition of endurance under the demands of challenges of all kinds. The 13th century Dominican friar Thomas Aquinas argued not only that courage is endurance under hardships of any kind whatever, but that for this reason, courage is the steady expression of all of the virtues of the human soul because a virtuous person does not take holidays from the good to dabble in behaviors that might be fun or momentarily exciting but also morally corrupting. We have observed that we human beings have a natural appetite or desire for what is good, and a natural aversion for what is dangerous or harmful. Courage is the virtue that manages the urge for aversion so that one remains steady and focused in hardship. Temperance is the virtue that manages the appetite of desire.

Temperance is “the righteous habit which makes a man govern his natural appetite for pleasures of the senses in accordance with the norm prescribed by reason.” The pleasures of concern here fall into three classes: those associated with the preservation of the individual, those associated with the perpetuation of the human race, and those associated with the well-being and comfort of a human life. Thus we see three attendant and subordinate virtues in harmony with temperance: abstinence, chastity, and modesty. Abstinence functions in relation to food and drink and here one must follow the counsel of reason because temperance in food and drink will vary from one person to another. Men in general need more food than do women in general. Athletes will need more food and drink than retired office workers, and so on. Abstinence avoids the vices of gluttony and drunkenness. The function of chastity is to regulate one’s disposition toward the sensual satisfactions that attend sexual reproduction, that is, to avoid the excesses occasioned by the vice of lust. Modesty is the virtue by which we manage the human passions that lie in us less violently than do the passions for food and drink, and for sex. It expresses itself in us as a kind of humility by which one’s interior life is set in order (and contributes importantly to inner peace). Modesty regards such things as style of life, manner of speech and dress, how one carries himself, and the like, and this helps us understand why temperance is a cardinal virtue.

Justice is considered the most important of the cardinal virtues because it regulates our interactions with others. “It is a moral quality or habit which perfects the will and inclines it to render to each and to all what belongs to them.” The virtue of charity inclines us to assist others out of our own means. Justice requires us to give to others what belongs to them. This includes normal and accepted social courtesies and manners, keeping one’s agreements with others, keeping one’s word and promises, keeping one’s hands off of others without their permission, and keeping one’s hands off of other people’s property. It has long been understood that no society can be free that does not hold secure the property rights of individuals. When government takes to itself the authority to determine how much of a man’s property he may keep, liberty is at an end.

Americans of our founding generation understood the importance of virtue in the people to the maintenance of a free and well-governed society. Certainly Americans of Basil Gildersleeve’s generation understood this, too. And of course, Gildersleeve himself understood the tradition of virtue ethics very well, and it gave rise to his admonition to “Grow, don’t climb.”

Posted on: April 11, 2023