The Principle of Federalism

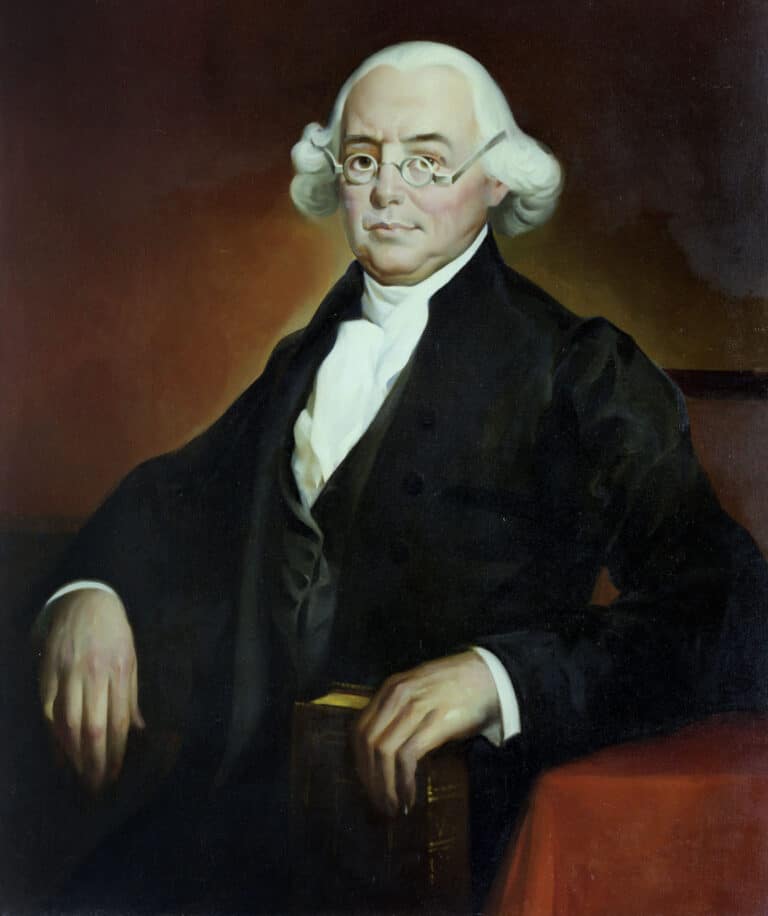

James Wilson was a Scottish-born Pennsylvanian who was one of the leading jurists in the early years after the ratification of the Constitution. He served on the Committee of Detail that produced the first draft of the Constitution at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787. He is regarded as the principal designer of the executive branch of government in the Constitution. Wilson was a nationalist who wanted the president to be elected by Americans considered as one national body of citizens, rather than as citizens of separate, sovereign states. This proposal was not going to pass out of the Convention because the United States was not a nation under the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, but a confederation of sovereign states, and there was little expressed desire to create a unitary nation with a sovereign, central government. So, having taken the general temper of his colleagues, Wilson proposed the electoral college as a state-based process for choosing a president. Wilson was one of the original six justices of the Supreme Court appointed by George Washington and, as the first professor of law at the College of Philadelphia (which became the University of Pennsylvania), taught the first course on the Constitution to President Washington and his cabinet in 1789 and 1790.

The Convention ended on 17 September, 1787 and nineteen days later, on 6 October, Wilson gave a speech defending the Constitution from critics. The speech was delivered in the yard of the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, where the Constitution had been approved just days before, and so his defense has come to be known as the State House Yard Speech. This speech is important in part because of its influence on the tone of debates about the Constitution that were to follow. The nationalists, who misleadingly called themselves “federalists,” showed a troubling tendency to use invective and censorship to bully into acquiescence those Americans who did not like the proposed Constitution. Though Wilson was a nationalist, he recommended the new Constitution to the minds of his countrymen with civility and rigor, considering the arguments of critics as honest expressions of concern about the new Constitution. However, civility and rigor in responding to critical analyses of one article or another of the Constitution would not have been sufficient to persuade critics convinced that the new federal government was given too much power for the sovereignty of the states to be secure. Wilson’s speech was influential because he based his case on the widely held principle of federalism, which many Americans thought to be imperiled by the new Constitution. In short, Wilson set out to confront first of all the objection that the new constitution upends the principle of federalism for this is the objection in light of which all other objections drew their force.

Wilson begins his refutation of criticisms of the proposed Constitution by seeking to allay fears that the new frame of government, if adopted, would grow over time into what was called “a despotism,” and he did this by identifying the essential difference between the state constitutions and the newly proposed federal Constitution. This difference, Wilson insists, is the fundamental principle of federalism upon which the new Constitution was based. When the people of the various states composed their constitutions, they gave to their representatives every right and authority they did not explicitly reserve. In other words, those actions which state governments were forbidden to undertake were written down in their constitutions, and where a right or authority was not forbidden, it was allowed. In the federal Constitution the principle is reversed, so the federal government has only those powers delegated in the Constitution, and where the Constitution is silent, the federal government has no authority. “Hence, it is evident, that in the former case [the states] everything that is not reserved is given; but in the latter [the federal government] the reverse of the proposition prevails, and everything which is not given is reserved.” James Madison famously said this very thing to the people of New York in Federalist 45: “The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite.” This principle would be enshrined in the new Constitution in the Tenth Amendment in 1791: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” It is difficult to overstate the importance of this principle to the adoption of the Constitution in the state ratification conventions.

When the Constitution was ratified and the new Congress seated in 1789, members of Congress set about immediately to escape the constitutional limits on their powers. We should recognize that despite the significance of the separation of powers in the Constitution, the three branches of the central government are three branches of the same government, and so an expansion of power for one is an expansion that may be enjoyed by all.[i] For example, in the Judiciary Act of 1789, that established a system of lower federal courts, the office of attorney general, and federal prosecutors and marshals, Congress gave to the Supreme Court authority to uphold or reverse decisions of state courts in matters regarding the constitutional validity of a federal law (see the Judiciary Act of 1789, section 25). This gave the federal government, through the Supreme Court, substantial power over state courts not contemplated in the Constitution and in violation of the principle of federalism as James Wilson presented it. Thomas Jefferson asserted the principle of federalism in 1791, writing in opposition to the establishment of a national bank on grounds that there is no grant of authority in the Constitution by which Congress may do it. “I consider the foundation of the Constitution as laid on this ground: That ‘all powers not delegated to the United States, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States or to the people’. To take a single step beyond the boundaries thus specifically drawn around the powers of Congress is to take possession of a boundless field of power, no longer susceptible of any definition.”

So, the first criticism of the Constitution that Wilson addresses after clarifying the principle of federalism is the fact that as written and approved in Philadelphia, the Constitution did not have a bill of rights, and so did not explicitly embrace the principle of federalism. The so-called anti-federalists insisted upon a bill of rights because they saw the Constitution as a classic “thin edge of the wedge” which at first causes no significant disruption of the reigning order but in time will split the thing apart. This is because the anti-federalists thought that the Constitution could be used to draw away the sovereignty of the states over time through artful interpretations of the document by the Supreme Court. A bill of rights that enumerates some of the important the rights we have by nature, and thus prior to any government, would set clear limits on federal power and thus protect the very rights of liberty that people hungry for power most want to suppress. The Constitution as ratified by the states in 1788/89 did not create a national sovereignty but a federation of sovereign states. In this arrangement, the federal government is but an agent of the states that created it and so has no sovereignty of its own.[ii] Americans objecting to the new Constitution asserted that it did not adequately protect against what they called “usurpation,” which is the exercise by the federal government of power not delegated to it in the Constitution. The Articles of Confederation did protect Americans from federal usurpation, and many feared that removing this protection was the real motive behind drafting a new Constitution at Philadelphia. Jefferson’s argument against establishing a national bank is that this would be a usurpation of power since no such authority was delegated to Congress in the Constitution. Here we find the supreme discipline that is required in order for a federal republic to work: every act of Congress that involves the exercise of undelegated power, usurpation, must be rejected, no matter how desirable the goal (if the presumed need is thought to be sufficiently great, then we amend the Constitution first in order to authorize Congress to act).[iii] If the federal agent is able to usurp the sovereignty of the states through repeated exercises of unlawful power, the states will cease to be sovereign and will be reduced to administrative districts of the center, and in such a case, the servant will have become the master, and the masters, servants. Wilson was convinced that this would not happen because the principle of federalism that guided the design of the proposed federal government made it impossible, and so a bill of rights that spelled it out would be redundant. Nevertheless, Wilson seems not to have minded much if there was a bill of rights; his concern was to prevent the absence of a bill of rights from blocking ratification of the Constitution in the several state conventions.

There was sharp disagreement about a bill of rights. George Mason, of the Virginia delegation, abruptly left the Philadelphia Convention “in an exceeding ill humor,” according to James Madison, precisely because the proposed Constitution had no bill of rights. Madison argued in Federalist 84 that what we call a bill of rights began as, and had always been, a codification of prerogatives wrested from a prince, often at the point of a sword, in favor of the rights of subjects (for example, Magna Carta). So a bill of rights has no place in a constitution wherein free, sovereign people are determining what will and will not be the powers of government. In any case, Madison contended, there are specific clauses throughout the Constitution that secure the rights of persons, like the specification for treason in Article III, section 3. Thomas Jefferson, writing from Paris, declared that “a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse.” Writing elsewhere, Jefferson asserted the value of a bill of rights to be its establishment of a common language in which Americans can discuss the political implications of our natural rights. In the end, Madison consented to draft a bill of rights to be recommended for inclusion in the Constitution by the first Congress.

Perhaps the most serious criticism Wilson considers is that the Constitution was purposefully designed to reduce the states to “mere corporations,” or administrative districts of the general government, and ultimately “to annihilate them.” There are two charges here: first, the Constitution will reduce the states from sovereign political societies to mere corporations; second, the Constitution will ultimately annihilate the states. Wilson addresses the second charge, but curiously ignores the first one. In the Declaration of Independence, we read in part: “… these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States….” In Article 1 of the Treaty of Paris, 1783, the British crown recognizes the independence of the former colonies this way: “His Brittanic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz. [then each state is named individually], to be free sovereign and Independent States; and he treats with them as such,…” It is these sovereign states that created a federal government, but those Americans who opposed adoption of the new Constitution were clear in their concern that this Constitution would fashion a government calculated to draw into itself the sovereignty of the states, leaving them as corporations, or administrative districts, of the central government. Wilson passes over this charge and attacks the second one.

The second charge, that the new government will eventually annihilate the states, is rebutted by observing that the processes for electing presidents, senators, and representatives all require the existence of state legislatures. For example, presidents are selected by electors of the states chosen by processes to be determined by the legislatures of the states, and senators, under the Constitution as first adopted, were chosen by the legislatures of the states. State legislatures were needed to set the qualifications for those who will elect members of the House of Representatives, and state legislatures have a role, though they are not absolutely required, in amending the document. However, there is no contradiction in states having legislatures while being mere corporations of the center, which is why Wilson’s neglect of the first of these two charges is lamentable.

Wilson finishes his speech saying: “Regarding it then, in every point of view, with a candid and disinterested mind, I am bold to assert, that this is the best form of government that has ever been offered in to the world.” It is clear throughout Wilson’s speech that from the moment the Constitution had been written, there were people who supported it and people who opposed it. Human affairs are nearly always more complicated than the simplistic versions of things we get in the press, and here we get a sense of what would become the complex processes in every state that led to a public understanding of the Constitution and, with some tight votes and occasional arm-twisting, to its ratification. We get also a fine demonstration of civic engagement that ends with excellent advice for how to interact with our fellow citizens, which is to examine matters of public importance from every point of view, with a candid and disinterested (we might say “objective”) mind.

_____________________________________________

[i] The late Justice Antonin Scalia once remarked of people who seek to take disagreements with the federal government to the Supreme Court: “Why are you coming to me? I’m a Fed.”

[ii] The assertion that the Constitution created a divided sovereignty is an artifice meant to confuse rather than to clarify. Sovereignty is the authority to act without the permission of another, and so it cannot be divided. In defense of the artifice of divided sovereignty, people will say that the Supremacy Clause in Article VI of the Constitution is a clear expression of sovereignty vested in the central government. But the assertion works only if we fail to read all of the words we find there. In relevant part we read: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; …shall be the supreme Law of the Land;…” (emphasis added). It is not the case that whatever law the central government passes is for that reason the supreme law of the land, but only those laws made in obedience to the powers both delegated and reserved by the Constitution (and thus, in Pursuance thereof). Thus a law issued without constitutional warrant is not only not supreme law, it is not law at all, but rather an illegal usurpation of power. How is this determined? The answer is in the Tenth Amendment which expresses the principle of federalism. Under the Constitution, sovereignty lies in the people of the states, and so a usurpation must be confronted by acts of citizenship in which the people of the several states, through their governments, advise the federal agent of the states that it has exceeded its delegated authority and so the offending legislation is unconstitutional and thus not law, or in the more pungent language of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798, “null, void, and of no force or effect.” This sounds bold in our time, maybe even more than bold, but our rights are not given us by government, for if they were, government could take them from us at its discretion. Our rights arise from our human nature, which exists prior to every human government, and so we establish governments as the means for protecting our rights. Constitutions do not interpret themselves, and they do not enforce themselves. This is the work of citizenship in a constitutional, federal republic.

[iii] We lack space here to explain why the “necessary and proper” clause of Article I, section 8 has no relevance to the discipline of citizenship required to check usurpations by Congress, since this involves explaining how the meaning of the phrase “necessary and proper” has been distorted by the courts. However, James Madison explains this well in his Report of 1800. A very good article on this issue, with links to Madison’s Report and his Virginia Resolutions of 1798, may be found here. https://tenthamendmentcenter.com/2017/07/16/james-madison-and-the-necessary-and-proper-clause/